Glycated hemoglobin levels (HbA1c) reflect the blood sugar control over the preceding 1-3 months and has been found in studies to correlate well with the development of diabetic complications.1 Periodontitis is an inflammatory disease initiated by an oral microbial film formerly known as plaque.2 The host's inflammatory response results in the destruction of the bone and soft tissue supporting the tooth.2 Periodontitis is now considered the 6th complication of diabetes due to the number of studies documenting its increased prevalence among diabetic patients.3 Periodontal treatment has shown a modest but significant reduction on HbA1c (-0.40%; 95% confidence interval) among diabetic patients but data in this meta-analysis were mostly from type 2 diabetic patients (T2DM).4 Treatment studies on type 1 diabetic (T1DM) patients have shown significant improvement in periodontal health, but this improvement is not reflected in the HbA1c levels like in T2DM patients.5-8

There are several differences between T1DM and T2DM. T1DM results from T-cell mediated pancreatic islet β-cell destruction which leads to absolute insulin deficiency.9 Serological markers of the autoimmune pathologic process or insulin autoantibodies are present in 85-90% of patients.9 T2DM on the other hand, occurs when insulin secretion is inadequate to meet the increased demand posed by insulin resistance.10 T2DM is commonly associated with inflammation, obesity and other features of insulin resistance.11 Although the development of these two types of diabetes is different, they both clinically manifest as an increase in blood sugar levels.

Clinically, patients with T2DM are frequently obese while those with T1DM are non-obese. The results of the Study of Health in Pomerania (SHIP) indicated that obesity was associated with both the extent and severity of periodontal disease along with markers of systemic inflammation in T2DM subjects.12 C-reactive protein (CRP) is primarily a non-specific marker of inflammation and its levels rise in response to infections, autoimmune diseases and malignant processes.13 Excessive periodontal disease and Body Mass Index are jointly associated with increased CRP levels in otherwise healthy, middle-aged adults.14

We report a 15-year-old female diagnosed with T1DM at age 8, during a diabetic ketoacidosis (DKA) episode. A second DKA episode occurred at age 11. She currently injects herself with premixed human insulin (70/30) twice a day, 40 units in the morning and 30 in the evening. She rarely monitors her blood sugar at home due to the high cost of glucose monitoring strips. The patient is 160 cm in height and weighs 53.7 kg. Her Body Mass Index (BMI=kg/m2) is 21.

Her last visit to the dentist was at 7 years old, before she was diagnosed with T1DM. Oral examination revealed severe bleeding of the gums with heavy calcular deposits (Figures 1a,1b). The patient also had halitosis (bad breath), but dental caries and tooth mobility were not observed. The patient was aware of her bleeding gums but denied knowing she had bad breath. She brushes her teeth three times a day and uses dental floss once a day. Initial treatment consisted of scaling and tooth polishing for 4 visits to reduce gingival bleeding and remove gross calculus deposits (Figures 2a, 2b), and to educate the patient on proper oral hygiene practices. During these visits, lessons learned from past diabetes camps she attended like: calorie counting, food exchange, insulin adjustment, injection techniques, blood glucose monitoring and other topics on diabetes self-management were reviewed. The patient was unable to return for further treatment until 20 months later.

Click here to download Figure 1a-bFigure 1a-b. Patient's initial oral examination revealed severe bleeding of the gums and heavy calcular deposits.

Click here to download Figure 2a-b

Figure 2a-b. Gum bleeding was significantly reduced after only 4 sessions of scaling but the traces of inflammation can still be seen on the marginal gingival and interdental papilla.

Definitive Treatment

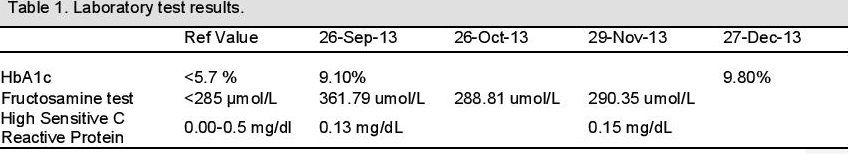

On follow-up after 20 months, a panoramic x-ray (Fig. 5) did not show any significant bone destruction around the teeth. The following serological tests were requested: glycated hemoglobin assay (HbA1c), fructosamine test (a measure of glycemic control over the previous 2-3 weeks), and high sensitive C-Reactive Protein (hsCRP).15 HbA1c was determined using high performance liquid chromatography while fructosamine was determined using a colorimetric reaction with nitrobluetetrazolium. The hsCRP was determined by the agglutination method. The patient was also referred to a physician to confirm if any undiagnosed diabetic complications were present.

Click here to download Table 1Table 1. Laboratory test results..

Click here to download Figure 5

Figure 5. Panoramic x-ray showing no caries and no obvious bone loss.

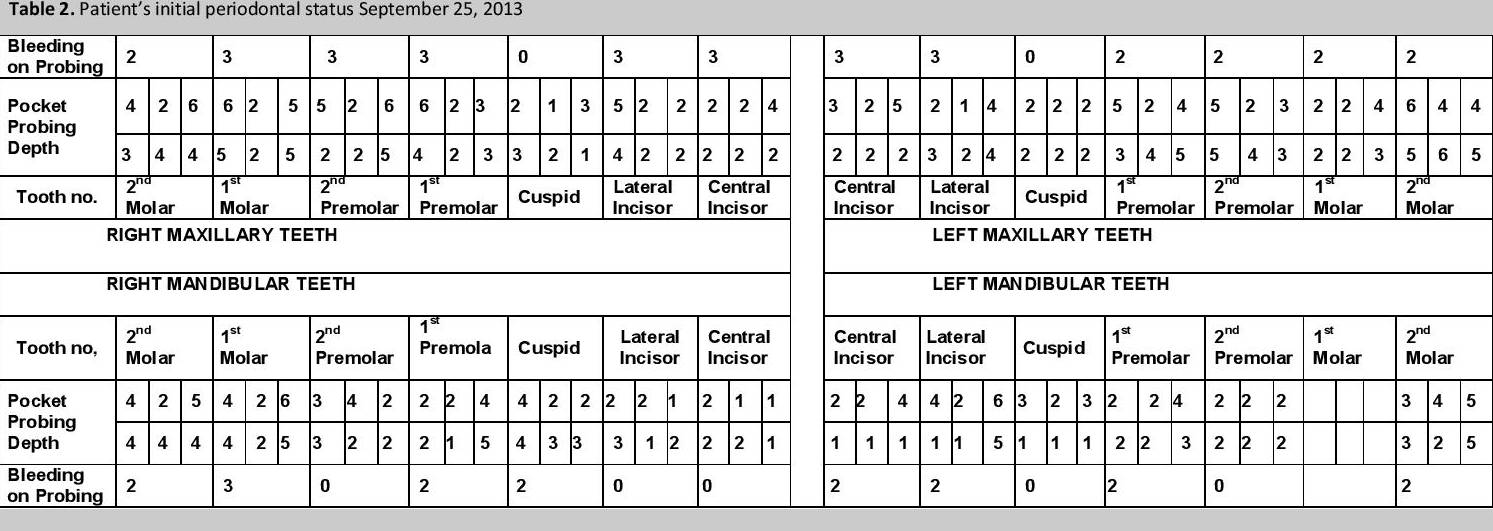

Pocket probing depth (PPD) was measured and recorded (Table 2). PPD is the distance between the marginal gingival and the bottom of the gingival sulcus (Figures 3a,3b) and is measured in 6 sites around the tooth, using a periodontal probe with calibrated marking to indicate depth in millimeters. Bleeding on probing (BOP) was given a score of: 1 when a dot of blood appears on the gingival margin following probing, 2 when a line of blood appears, and 3 when blood overflowed the gingival margin (Figure 3b) and is indicative of the degree of inflammation that is present. Tooth mobility is a measure of the amount of alveolar bone loss around the tooth; none was detected, consistent with the panoramic x-ray mentioned earlier. A PPD of >4 mm is indicative of the presence of periodontitis. Oral hygiene instructions were reviewed together with diabetes self-management strategies.

Click here to download Table 2Table 2. Patient's initial periodontal status.

Click here to download Figure 3a-b

Figure 3a-b. Pocket probing prior to root planting procedure. tendency of the gums to bleed is manifest and gingival architecture reveals pronounced swelling especially in the interdental papilla areas .

The patient was provided with the following prior to start of treatment: insulin and glucose strips for blood glucose home monitoring, toothbrushes, triclosan /copolymer toothpastes, dental floss, interdental toothbrushes, 0.12% chlorhexidine gluconate mouthwash (up to 6 weeks post-root planing) and a 0.075 cetylpridinium chloride mouthwash (for use after 6 weeks post-root planing). Patient was asked to continue brushing her teeth three times a day and to floss at least once a day. She was also instructed to use the mouthwash twice a day. Root planing was performed for the maxillary teeth and the mandibular teeth on two separate occasions, within a span of 1 week. The patient was asked to keep a record of her blood glucose levels, food intake, insulin dose and oral hygiene practices.

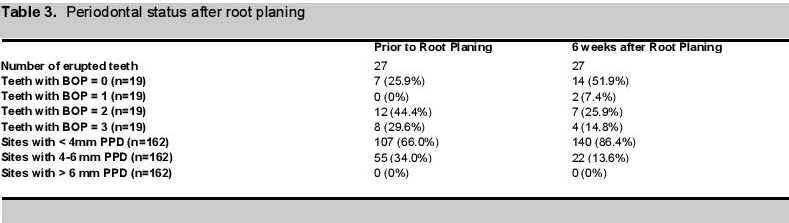

Treatment OutcomesOrally, diminution of inflammation and bleeding required 4 sessions of scaling (Figs 2a, 2b). Following root planing, there was an ~60% decrease (from 55 to 22) in sites with 4-6 mm PPD and there was an ~30% decrease (from 20 to 13) in the number of teeth with bleeding on probing score greater than 0 (Table 3, Figures 4a, 4b).

Click here to download Table 3Table 3. Periodontal status after root planing.

Click here to download Figure 4a-b

Figure 4a-b. Marked resolution of inflammation on the interdental papilla areas. Gingival bleeding was markedly reduced but gingival margin still appears swollen.

Serologically, there was a decrease (~20%) in fructosamine levels (from ~362 umol/L to ~289umol/L ) 1 month following periodontal therapy, which remained relatively constant. HbA1c levels increased (from 9.1% to 9.8) three months from the time of the initial visit while hsCRP levels also slightly increased from 0.13 mg/dL to 0.15 mg/dL over this time.

Subjectively, the patient reported that her quality of life greatly improved. She stated that she overcame her shyness and fear of talking close to people, now laughs out loud without covering her mouth and is considered one of the "noisy girls" in her class.

This case report is important because it provides a demonstration of how conservative periodontal therapy can improve the quality of life an adolescent T1DM patient. Treatment was conservative and relatively inexpensive and clearly beneficial to the patient. The limitation of this case report lies in the single subject and that insulin resistance was not directly measured in order to ascertain its presence.

Poor response to periodontal therapy was observed during the initial treatment and four sessions of scaling and polishing was required to reduce gingival bleeding. This was again observed when response to root planing did not result in the improvement of all pocket depths greater than 4 mm and several teeth continued to exhibit BOP greater than 0. Failure on the part of the patient to follow oral hygiene instructions and/or the dentist's inability to clean the root surfaces well may account for these results.

Another possible reason which we propose is the presence of insulin resistance in the patient. The patient was observed to have considerably more fat deposits compared to a previous type 1 diabetic we treated similarly.16 An analysis of the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey III data showed that overweight individuals with IR in the highest quartile exhibited more severe periodontitis compared to subjects with high Body Mass Index and low IR. 17

Insulin resistance is thought to be associated only in T2DM but not in T1DM because insulin resistance has been documented in the development of T2DM but not on T1DM. Furthermore few studies have studied insulin resistance in T1DM patients because tools for measuring insulin resistance in T2DM are not applicable to T1DM, and those that are applicable are costly and invasive.18 A hospital-based study on adult type 1 diabetics in the Philippines, using estimated glucose disposal rate, showed the prevalence of IR was 53% in the studied population.18

The patient's HbA1c increased from 9.1% from baseline to 9.8% after 3 months. It is difficult to reconcile the different trends in the HbA1c test and the fructosamine test at first. However, if you consider the proximity of the fructosamine test to the root planing procedure, the reduction can certainly be attributed in part to periodontal treatment. There may be several reasons for the lack of improvement in the HbA1c: (1) the improvement in her oral status might have caused an increase in food intake; (2) the treatment period coincided with the holiday season (Christmas) where people eat more to celebrate; and (3) An adjustment in her insulin dose may have been warranted since baseline HbA1c was already elevated.

Conservative management of periodontitis using root planing is effective not only in reducing the oral health outcomes and appears to reduce blood sugar in the short term but not using longer term tests like HbA1c.

1. Davidson MB, Schriger DL, Peters AL, Lorber B. Glycosylated hemoglobin as a diagnostic test for type 2 diabetes mellitus. JAMA. 2000;283(5):606-607.

2. Van Dyke TE. The management of inflammation in periodontal disease. J of Periodontol. 2008;79(8):1601-1608.http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1902/jop.2008.080173.

3. Löe H. Periodontal disease: The sixth complication of diabetes mellitus. Diabetes Care. 1993;16(1):329-334. http://dx.doi.org 10.2337/diacare.16.1.329.

4. Simpson TC, Needleman I, Wild SH, Moles DR, Mills EJ. Treatment of periodontal disease for glycaemic control in people with diabetes. Aust Dent J.2010;55(4):472-474. http://dx.doi.org/10.1111/j.1834-7819.2010.01273.

5. Aldridge JP, Lester V, Watts TL, Collins A, Viberti G, Wilson RF. Single-blind studies of the effects of improved periodontal health on metabolic control in type 1 diabetes mellitus. J.Clin Periodontol.1995;22(4):271-5. http://dx.doi.org/10.1111/j.1600-051X.1995.tb00147.x.

6. Smith GT, Greenbaum CJ, Johnson BD, Persson GR. Short-term responses to periodontal therapy in insulin-dependent diabetic patients. J of Periodontol.1996;67(8): 794-802.http://dx.doi.org/10.1902/jop.1996.67.8.794.

7. Westfelt E, Rylander H, Blohme G, Jonasson P, Lindhe J. The effect of periodontal therapy in diabetics. Results after 5 years. J ClinPeriodontol.1996; 23(2): 92-100. http://dx.doi.org/10.1111/j.1600-051X.1996.tb00540.x.

8. Llambés F, Silvestre FJ, Hernández-Mijares A, Guiha R, Caffesse R. The effect of periodontal treatment on metabolic control of type 1 diabetes mellitus. Clin Oral Investig.2008;12(4):337-43. http://dx.doi.org/10.1007/s00784-008-0201-0.

9. Craig ME, Hattersley A and Donaghue KC. Definition, epidemiology, and classification of diabetes in children and adolescents. Pediatr Diabetes. 2009;10(Suppl. 12):3-12. http://dx.doi.org/10.1111/j.1399-5488.2009.00568.x.

10. Druet C, Tubiana-Rufi N, Chevenne D, Rigal O, Polak M, Levy-Marchal C. Characterization of insulin secretion and resistance in type 2 diabetes of adolescents. J. Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2006;91(2):401-404. http://dx.doi.org/10.1210/jc.2005-1672.

11. Miller J, Silverstein JH, Rosenbloom AL. Type 2 diabetes in the child and adolescent. In: LIFSHITZ F (ed) Pediatric Endocrinology: Fifth edition, volume 1. New York: Marcel Dekker 2007: pp 169-188.

12. Meisel P, Wilke P, Biffar R, Holtfreter B, Wallaschofski H, Kocher T. Total tooth loss and systemic correlates of inflammation: role of obesity. Obesity (Silver Spring).2012; 20(3): 644-650. http://dx.doi.org/10.1038/oby.2011.218.

13. D'Aiuto F, Orlandi M, Gunsolley JC. Evidence that periodontal treatment improves biomarkers and CVD outcomes. Jof Clin Periodontol. 2013;40(Suppl.14): S85-S105.http://dx.doi.org/10.1111/jcpe.12061.

14. Slade GD, Ghezzi EM, Heiss G, Beck JD, Riche E, Offenbacher S. Relationship between periodontal disease and C-reactive protein among adults in the Atherosclerosis Risk in Communities study. Arch Intern Med. 2003;163(10): 1172-1179. http://dx.doi.org/10.1001/archinte.163.10.1172.

15. Mealey BL, Ocampo GL. Diabetes mellitus and periodontal disease. Periodontol 2000. 2007;44(1):127-153. http://dx.doi.org/10.1111/j.1600-0757.2006.00193.x.

16. Ofilada EJL. Managing periodontitis in type 1 diabetic patients improve glycemic control. St. Luke's Journal of Medicine. In press.

17. Genco RJ, Grossi SG, Ho A, Nishimura F, Murayama Y. A proposed model linking inflammation to obesity, diabetes, and periodontal infections. J of Periodontol Online. 2005;76 (11-s):2075-2084. http://dx.doi.org/10.1902/jop.2005.76.11-S.2075.

18. Barrera JR, Jimeno CA, Paz-Pacheco E. Insulin resistance among adults with type 1 diabetes mellitus at the Philippine General Hospital. J Diabetes Metab. 2013;4:10. http://dx.doi.org/10.4172/2155-6156.1000315.

Authors are required to accomplish, sign and submit scanned copies of the JAFES Declaration that the article represents original material that is not being considered for publication or has not been published or accepted for publication elsewhere.

Consent forms, as appropriate, have been secured for the publication of information about patients; otherwise, authors declared that all means have been exhausted for securing such consent.

The authors have signed disclosures that there are no financial or other relationships that might lead to a conflict of interest. All authors are required to submit Authorship Certifications that the manuscript has been read and approved by all authors, and that the requirements for authorship have been met by each author.