An astounding 382 million people are estimated to be living with diabetes mellitus in 2013, with 72 million in Southeast Asia.1 In addition, China and India are the two countries with the highest numbers of people with diabetes.

Medical nutrition therapy is a cornerstone of the management of diabetes mellitus (DM). Emphasis is placed on the ability to recognize and estimate the amount of carbohydrate in food, as the intake of carbohydrate has the largest impact on glycemic control.2 Indeed, for people with type 1 DM, it is recommended that prandial insulin dose should be matched with carbohydrate intake, in addition to pre-meal glucose and anticipated activity.2 This approach may also be extended to people with type 2 DM on a multiple daily insulin dosing schedule.

There have been numerous tools developed in the Western Hemisphere to evaluate an individual's general diabetes knowledge, diabetes numeracy skills and carbohydrate knowledge.3-5 In contrast, standardized tools for the study of diabetes knowledge in Asian populations are not common. While quizzes targeted at evaluating general diabetes knowledge and numeracy skills can be applied universally, carbohydrate knowledge quizzes developed for Western populations may not be suitable for Asians. The typical Asian diet is considerably different, with more varied carbohydrate choices. For example, rice and rice products are the staple carbohydrate in most Asian countries including Singapore, whereas cereal, cereal products (including bread) and potatoes account for the bulk of carbohydrate intake in Western countries.6,7 Furthermore, the conventional way of assessing each individual's carbohydrate knowledge by a dietitian is time-consuming and may be fraught with inconsistencies, depending on the experience and training of the dietitian. In the primary care setting, there may also be a lack of access to registered dietitians.

We thus aimed to develop and validate a carbohydrate and insulin dosing knowledge quiz for adult patients with DM who consume a predominantly Asian diet.

Development Quiz

The structure of the quiz was based on the PedCarbQuiz, which consists of seven domains: 4 on carbohydrate knowledge and 3 on insulin dosing.5 The carbohydrate knowledge domains include recognition of carbohydrates in food, estimation of carbohydrates in a single food, food label reading and estimation of carbohydrate in a meal. The insulin dosing domains include use of insulin dose correction based on blood glucose level, use of insulin to carbohydrate ratio in insulin dosing and calculation of total insulin dose for a meal.

Food items were drawn from review of existing patient food logs and from the study dietitians' experience of food that was commonly reported to be eaten during diet counselling sessions.

As a multi-racial country, the average daily diet in Singapore consists of food with Chinese, Malay, Indian, as well as regional Southeast Asian culinary influences. Representative food items commonly eaten by Chinese, Malay and Indian ethnic groups, and available at frequently patronized hawker centers, coffee shops and food courts were selected.6 Photographs of the food items representing portion size were included for each question to avoid confusion between foods with similar sounding colloquial names.

Most domains contained 8 questions, with the exception of 24 items for recognition of carbohydrate in a single food item and 2 questions for calculation of total insulin dose for a meal. This yielded a maximum total score of 64 for the quiz. The quiz was designed such that the odd-numbered questions mirrored the even-numbered ones. The quiz was then pre-tested in a group of 5 DM patients and non-study dietitians to assess ease of administration and clarity. The final quiz was designed to be self-administered and completed in 15 to 20 minutes. The quiz is appended in the online supplement.

Study SubjectsThe study was approved by the National Healthcare Group Domain Specific Review Boards (Singapore). Subjects were sequentially recruited from patients attending a diabetes centre in a single institution. We included English-literate participants who were at least 21 years of age, diagnosed with diabetes mellitus and treated with prandial insulin (short- or rapid-acting, including pre-mixed), regardless of type of diabetes. Informed consent was obtained for all subjects. Subjects who were unable to give or declined consent were excluded.

Study ProceduresThe recruited subjects were given the self-administered quiz after informed consent was obtained. Each correct answer was equivalent to 1 mark; for carbohydrate counting domains (single food and in a meal), ½ mark credit was given for answers close to the correct one.

Expert assessment for the carbohydrate domains was performed by the study dietitians (M.Y. and P.K.) who were blinded to the results of the quiz through a semi-structured subject interview. The study dietitians were asked to rate the knowledge of the subject in each of the carbohydrate domains using a 7-point scale, ranging from "not at all" to "very well." For the insulin dosing domains, the usual diabetes physician of the subject, who was also blinded to the quiz results, was asked to rate insulin dosing knowledge for each domain on a 7-point scale.

The expert assessments were correlated with the quiz results by the combined carbohydrate domains, the combined insulin dosing domains and overall total.

Chart review was performed to obtain demographic information (including age, gender and ethnic group), diabetes duration, insulin regimen and HbA1c within 3 months of the quiz administration.

Statistical AnalysisResults are expressed as median (interquartile range) for non-categorical variables and number of patients (percentage) for categorical variables. Respondents were categorized based on the median knowledge quiz score. Comparison of the characteristics of subjects with scores equal to, below and above the median score was done using the Mann Whitney U test for non-categorical variables and chi-square test for categorical variables

Two methods were used to assess reliability of the quiz by measuring internal consistency: calculation of Cronbach a and determination of split half reliability by Guttman split half coefficient between the two equivalent halves (odd-numbered vs. even numbered halves).

Criterion related validity was assessed by calculating Spearman correlation between the quiz scores and HbA1c, and quiz scores and expert (healthcare provider) assessments (for combined carbohydrate and insulin dosing domains and in total).

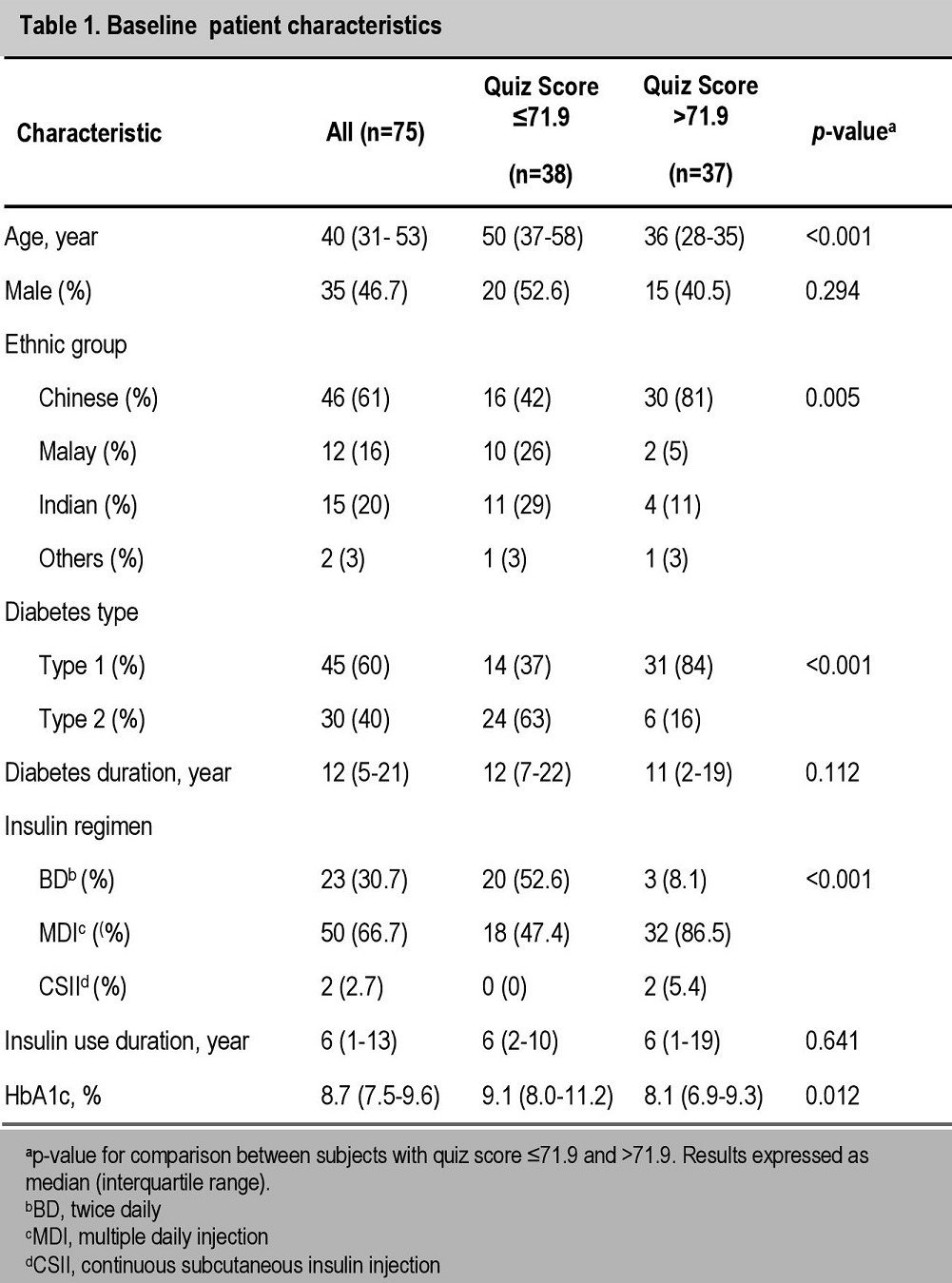

Study SubjectsAll 75 recruited subjects were able to complete the study. Subject characteristics are shown in Table 1. The study subjects represented all 3 major ethnic groups in Singapore, and included both type 1 and type 2 DM. Majority of the subjects were on multiple daily insulin dosing regimens.

Click here to download Table 1Table 1. Baseline patient characteristics

Quiz and Healthcare Provider Scores

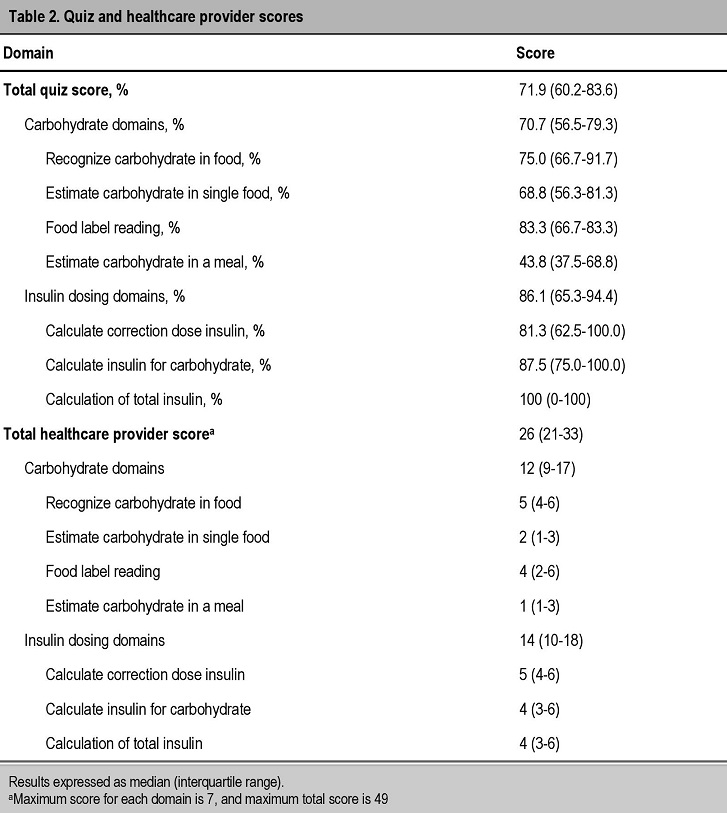

The median quiz score was 71.9% (range 60.2 to 83.6), while the median total healthcare provider score was 26 out of a maximum total of 49 (range 21 to 33). The quiz and healthcare provider scores for each domain are shown in Table 2.

Click here to download Table 2Table 2. Quiz and healthcare provider scores

The subjects performed better in the simpler carbohydrate compared to the more complex carbohydrate domains. Scores for recognizing carbohydrate in food was significantly higher than estimating carbohydrate in a single food (p<0.001) and estimating carbohydrate in a meal (p<0.001). Food label reading scores were also higher than estimating carbohydrate in a single food (p<0.001) and estimating carbohydrate in a meal (p<0.001). The subjects also scored better in the recognition of carbohydrate in a single food compared to a meal (p<0.001). There was no difference in scores between recognizing carbohydrate in food and food label reading (p=0.386).

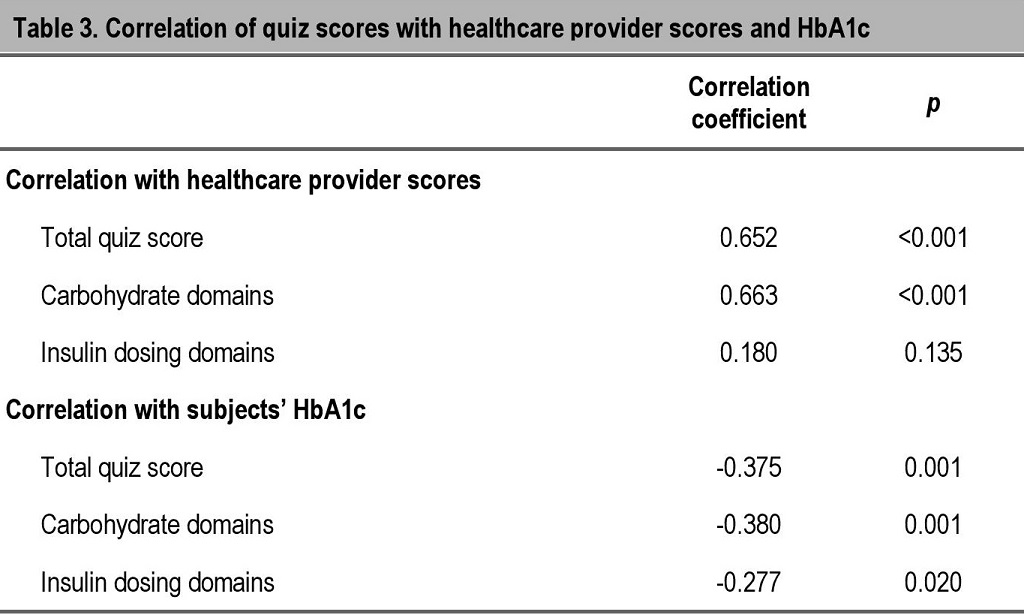

There was a significant, albeit weak to moderate negative correlation of the total quiz,, carbohydrate domain and insulin dosing domain scores with the subjects' HbA1c. Similarly, the total quiz and carbohydrate domain scores had strong and significant positive correlation with the healthcare provider assessments, which was not observed in the insulin dosing domain (Table 3).

Click here to download Table 3Table 3. Quiz and healthcare provider scores

Quiz Reliability

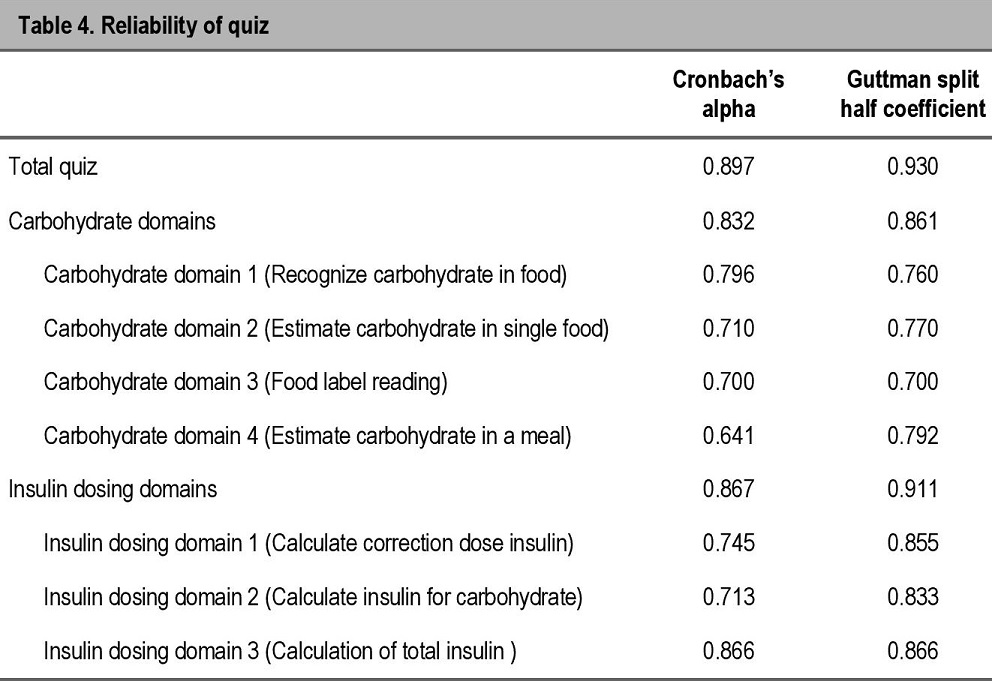

Cronbach α was 0.897 for the whole quiz, with a range of 0.641 to 0.866 for individual domains. Guttman split half coefficient was 0.930 for the whole quiz, with a range of 0.700 to 0.866 for individual domains (Table 4). These results indicate good internal consistency and split half reliability respectively.

Click here to download Table 4Table 4. Quiz and healthcare provider scores

Comparison of subjects with higher versus lower quiz scores

We used the median of 71.9% as a cut-off to divide the group into higher and lower quiz scores. Subjects who were younger, with type 1 DM, on more complex insulin regimens and with lower HbA1c scored better on the quiz. No significant difference was found between the two groups in terms of gender, duration of diabetes or duration of insulin use (Table 1).

Most subjects with type 1 DM are on multiple daily insulin injection regimens for diabetes management. The majority of patients with type 2 DM start with lifestyle measures and oral hypoglycemic agents for glycemic management. Subsequently, many require insulin to maintain good control, frequently starting with basal insulin and then progressing to basal-bolus type regimens similar to that used in type 1 diabetes.8,9 However, many patients do not practice flexible insulin dosing. This may be due to the lack of carbohydrate knowledge, numeracy skills, education and confidence in self-adjustment of insulin dose, among other reasons.

Central to flexible insulin dosing would be the ability to estimate the amount of carbohydrates in commonly eaten food, and the numeracy skills to estimate the insulin dose appropriate for the food to be eaten and for the correction dose based on pre-meal glucose. Even with fixed dose insulin regimens, the ability to recognize carbohydrates and estimate carbohydrate amounts in food is important to allow regular distribution of carbohydrates throughout the day. Thus, an objective tool to assess these key knowledge elements is crucial.

To the best of our knowledge, this is the first tool developed and validated for patients consuming a Southeast Asian diet. Some advantages of this tool are that it is brief, allows self-administration and includes visuals by way of food photographs. We also tested the calculation of insulin correction dose based on pre-meal glucose by two different methods: one following a correction scale and another by using an insulin sensitivity factor and a target glucose level. This allowed us to assess subjects with different practices. The PedCarbQuiz only utilized a correction scale.5

While attempts were made to include food commonly consumed by the different ethnic groups, it is possible that some items were not commonly eaten by others. However, in the melting pot food culture of Singapore, since we included commonly available foods, most people would be at least be familiar with the different food items. Furthermore, with increasing globalization, international travel and the availability and popularity of many of these food items worldwide, this quiz may also be applied to people with diabetes who enjoy ethnic variety in their food choices.

Overall, the quiz had good reliability (good internal consistency and split-half reliability) and validity (correlation with HbA1c and healthcare provider assessments). However, insulin dosing domains were not significantly correlated with healthcare provider assessment. A possible reason is that many of the study subjects do not routinely adjust insulin on their own, and may not be familiar with how it is done. Accurate assessment of these subjects' numeracy skills may be challenging since they did not self-adjust insulin regularly. Since healthcare provider assessment for the insulin domains were performed by the subjects' usual physicians, wider inter-physician assessment variability may be observed. In contrast, less variability may be seen between the 2 study dietitians for the carbohydrate domains. We attempted to minimize variability in ratings by having detailed descriptions for each point on the rating scale.

We found that subjects with higher quiz scores had lower HbA1c results. This may indicate that better knowledge had translated to better glycemic control. While knowledge alone is insufficient for good glycemic control, it is also clear that the lack of it would preclude the ability to follow a flexible insulin dosing regimen recommended in many guidelines.10,11 This quiz may then be used as a screening tool to identify subjects who are deficient in the necessary health literacy and numeracy skills for targeted education, with greater attention paid to domains with lower scores. As an example, subjects who do well at identifying carbohydrates in food but fare poorly at carbohydrate counting may attend advanced carbohydrate counting classes, while those who are not able to identify carbohydrates in food or read food labels may be more suited for basic carbohydrate counting classes.

Our study demonstrated the development and validation of a new carbohydrate and insulin dosing knowledge quiz in a multi-ethnic population of diabetic adults with on prandial insulin. It addresses an important gap in the current management of this population of patients. It may be applied within the Southeast Asian region, in migrant Asian populations, as well as to individuals who consume a more cosmopolitan diet. There are numerous potential uses of the quiz, including as a screening tool for knowledge gaps before intensifying insulin therapy and as an objective assessment tool following educational interventions.

AcknowledgmentsWe would like to express our gratitude to all the physicians and nurses at the Khoo Teck Puat Hospital Diabetes Clinic who assisted in recruiting and rating the study subjects. We would like to acknowledge and thank the patients who participated in this study.

Statement of AuthorshipA.K., A.N., M.Y. and P.L. contributed substantially to the conduct of the study, including conception and design, acquisition and analysis of data and drafting of the manuscript. C.S. and K.G. made significant contributions to the critical revision of the article. All authors have given approval to the final version submitted.

Conflict of InterestAll the authors have no conflict of interest to declare with respect to the work carried out in this paper.

Funding SourceThis study was funded by the Alexandra Health Enabling Grant (Singapore).

1. International Diabetes Federation. IDF Diabetes Atlas, 6th ed. Brussels, Belgium: International Diabetes Federation, 2013.

2. American Diabetes Association. Standards of medical care in diabetes-2014. Diabetes Care. 2014:37(Suppl 1):S14-80. http://dx.doi.org/10.2337/dc14-S014. 3. Fitzgerald JT, Funnell MM, Hess GE, et al. The reliability and validity of a brief diabetes knowledge test. Diabetes Care. 1998;21(5):706-10. http://dx.doi.org/10.2337/diacare.21.5.706. 4. Huizinga MM, Elasy TA, Wallston KA, et al. Development and validation of the Diabetes Numeracy Test (DNT). BMC Health Serv Res. 2008;8:96. http://dx.doi.org/10.1186/1472-6963-8-96. 5. Koontz MB, Cuttler L, Palmert MR, et al. Development and validation of a questionnaire to assess carbohydrate and insulin-dosing knowledge in youth with type 1 diabetes. Diabetes Care. 2010;33(3):457-62. 6. Health Promotion Board. Report of the National Nutrition Survey 2010. Singapore: Health Promotion Board, 2013. 7. Public Health England. National Diet and Nutrition Survey. Results from Years 1-4 (combined) of the Rolling Programme (2008/2009-2011/12). London, UK: Public Health England, 2014. 8. Turner RC, Cull CA, Frighi V, et al. Glycemic control with diet, sulfonylurea, metformin, or insulin in patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus: Progressive requirement for multiple therapies (UKPDS 49). UK Prospective Diabetes Study (UKPDS) Group. JAMA 1999;281(21):2005-12. 9. Holman R, Farmer A, Davies M, Levy J, Darbyshire J, Keenan J, et al for the 4-T Study Group. Three-Year Efficacy of Complex Insulin Regimens in Type 2 Diabetes. N Engl J Med. 2009;361:1736-47. http://dx.doi.org/10.1056/NEJMoa0905479. 10. Bloomgarden ZT, Karmally W, Metzger MJ, et al. Randomized, controlled trial of diabetic patient education: improved knowledge without improved metabolic status. Diabetes Care. 1987;10(3):263-72. http://dx.doi.org/10.2337/diacare.10.3.263. 11. Davies MJ, Gagliardino JJ, Gray L, et al. Real-world factors affecting adherence to insulin therapy in patients with Type 1 or Type 2 diabetes mellitus: A systematic review. Diabet Med. 2013;30(5):512-24. http://dx.doi.org/10.1111/dme.12128.Authors are required to accomplish, sign and submit scanned copies of the JAFES Declaration that the article represents original material that is not being considered for publication or has not been published or accepted for publication elsewhere.

Consent forms, as appropriate, have been secured for the publication of information about patients; otherwise, authors declared that all means have been exhausted for securing such consent.

The authors have signed disclosures that there are no financial or other relationships that might lead to a conflict of interest. All authors are required to submit Authorship Certifications that the manuscript has been read and approved by all authors, and that the requirements for authorship have been met by each author.