Queenie G. Ngalob, MD

Unit 1805 Manila Astral Tower

Taft Avenue Corner Padre Faura St. Ermita Manila, Philippines 1004

Email address: queenngalob@gmail.com

e-ISSN 2308-118x

Printed in the Philippines

Copyright © 2013 by the JAFES

Received April 1, 2013. Accepted October 12, 2013.

The traditional binary classification of gender is repeatedly challenged throughout history with the presence of transgenders. Under the umbrella of transgenderism is transsexualism which pertains to individuals who identify with or desire to become the opposite sex. Transsexualism or Gender Dysphoria is classified as a medical condition under ICD 10 and DSM-5. The proposed treatment is sex reassignment that includes all treatments carried out to adapt to the desired sex. Sex reassignment involves a multidisciplinary approach wherein the psychiatrist or mental health practitioner, endocrinologist and surgeon play active roles. Certain legal and ethical issues exist in the treatment of transsexualism. This article provides a review of psychological, medical and surgical issues in the evaluation and treatment of Transgender individuals, with an Asian perspective, and in the context of an actual case.

Key words: gender dysphoria, transsexualism, transgender

Sex is a biological construct which characterizes maleness or femaleness. It is best identified by chromosomes, hormones and genitalia. Sex is assigned at birth. Gender is a social construct and refers to the cultural patterns of behavior labeled as masculine or feminine. Gender identity is a person’s fundamental sense of being a man, a woman or the “other” gender.1-3

Sex and gender identity are usually in agreement. On occasion, sex and gender may be incongruent and result in distress called gender dysphoria.3 This gives rise to transgenderism, the umbrella term for persons whose gender identity, expression or behavior do not conform to that typically associated with their sex.2 Examples of transgenders include transvestites, gender queer and transsexuals. Transvestites are individuals who have sexual arousal with cross-dressing but do not want to become the opposite gender. Gender queer individuals believe that they transcend the binary gender labels.2

This paper focuses on transsexuals, or individuals who identify or desire to live and be accepted as members of the opposite sex. Often they wish to alter their bodies using hormones or surgery, though this is not a requirement for diagnosis.1-4 Biologically male persons who desire to be female are termed MTF (male to female) or transsexual women. Biological females who wish to be males are FTM (female to male) or transsexual men. 1

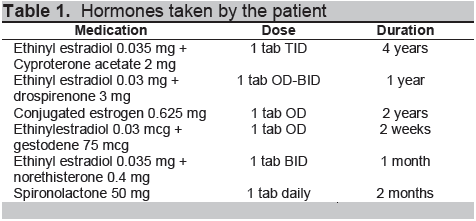

The patient is a 23-year-old male who consults for hormonal therapy. At 5 years old, the patient identified with the female gender and felt that he was a girl trapped in a boy’s body. He was fond of playing dolls and had affinity for his mother’s things. Growing up, he was often bullied because of his variant behavior. At 17 years old, he started to wear feminine clothes and grew his hair long. At 18 years old, he started to take feminizing hormones at the advice of friends and without medical consult. He has been taking oral contraceptive hormones for the past 5 years (Table 1).

Click here to download Table 1

Table 1. Hormones taken by the patient

Three months after starting these hormones, he noticed decreased acne and facial oil, slower growth of facial and leg hair, breast tenderness and enlargement, weight gain and fat accumulation in the hips, thighs and arms.

He has occasional dizziness, headache, sleepiness, mood swings, epigastric pain and decrease in libido and frequency of morning erections. He has no other illnesses and has a family history of hypertension, diabetes and cancer. He is a graduate student, a past smoker and occasional alcohol beverage drinker.

Pertinent in the physical examination is a body mass index of 23.7 kg/m2. He has full upper arms, abdomen, hips and thighs. He had no visible facial hair, but he admits to undergoing laser treatment for these. The patient did not consent to a breast examination but claims that he wears a cup A bra size for breasts likened to teenager. He has fine terminal hair in the forearms and coarse terminal hair in the lower extremities.

The patient consulted to ask these questions:

1.) Am I taking the right hormones?

2.) What are the long-term effects on my body?

3.)

If I wish to undergo surgery, how should I go about it?

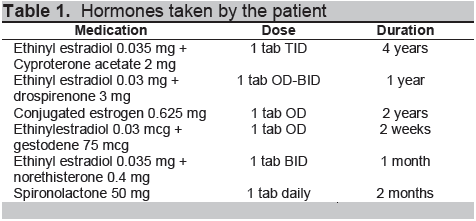

(Table 2)

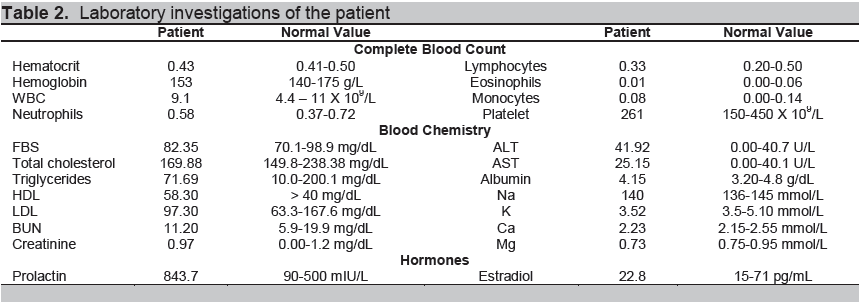

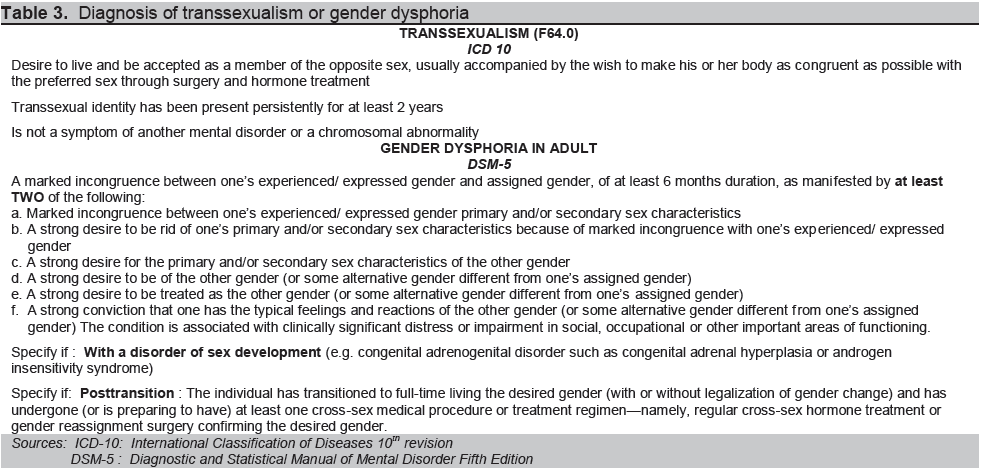

Transsexualism is listed in the International Classification of Diseases (ICD) 10.5 In psychiatry, it is termed Gender Dysphoria (GD) under the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders Fifth Edition (Table 3),3 criteria for which are met by the patient. Assessment for the patient is Transsexualism or Gender Dysphoria in adult.

No formal epidemiologic studies have been done on transsexuals. Current data are likely underestimates because these are mostly based on self-identified individuals or consults at gender clinics.6 In western countries, there are as many as 1:7,400-42,000 MTF and 1:30,400-104,000 FTM transsexuals. 7-11 In Singapore, the reported prevalence is 1:2,900 for MTF and 1:8,300 for FTM.12 Across different countries, MTF transsexuals are at least twice as many as FTM. In the Philippines, no estimates are currently published. Many European countries,13 some US states,14 and Asian countries Japan, South Korea, Singapore and Vietnam15 allow legal changes in name and gender of transsexuals. In the Philippines 16, 17 and Malaysia15 such legal changes are not allowed.

Click here to download Table2

Table 2. Laboratory investigations of the patient

Click here to download Table 3

Table 3. Diagnosis of transsexualism or gender dysphoria

The proposed treatment for transsexualism is sex reassignment. It includes all treatments carried out to adapt to the desired sex.1 Several guidelines aim to standardize sex reassignment such as recommendations from the Italian Society of Andrology and Sexual Medicine- National Observatory of Gender Identity (SIAMS-ONIG),18 the World Professional Association for Transgender Health which was formerly called the Harry Benjamin International Gender Dysphoria Association (HBIGDA)6 and the Endocrine Society.1

Sex reassignment is a multidisciplinary process. Based on current guidelines, patients should first be evaluated by a mental health practitioner or psychiatrist before an endocrinologist gives hormonal treatment. The final stage is surgical therapy.

Sex reassignment requires five processes –diagnostic assessment, psychotherapy and counseling, real life experience, hormone therapy and finally sex reassignment surgery.1 The psychiatrist is involved in the first three steps.

The first task is to diagnose transsexualism or gender dysphoria. The psychiatrist must distinguish it from differential diagnoses such as body dysmorphic syndrome, transvestic fetishism, schizophrenia or borderline personality disorder. Concomitant psychopathologies such as mood and anxiety disorders should also be identified.1,6,19,20 These comorbidities can be significant sources of distress and can complicate the process of sex reassignment if left untreated. If severe, addressing them should be prioritized.1 Second, the psychiatrist conducts psychotherapy for those in need of it. Psychotherapy can help an individual explore gender concerns and find ways to alleviate dysphoria by improving body image and promoting resilience. 6 The third step is the real life experience (RLE) or the act of fully adopting the desired gender role in everyday life which includes clothing, roles and tasks. It tests the person’s resolve, capacity to function, and adequacy of supports. Twelve months of RLE is recommended before proceeding with irreversible treatments.1

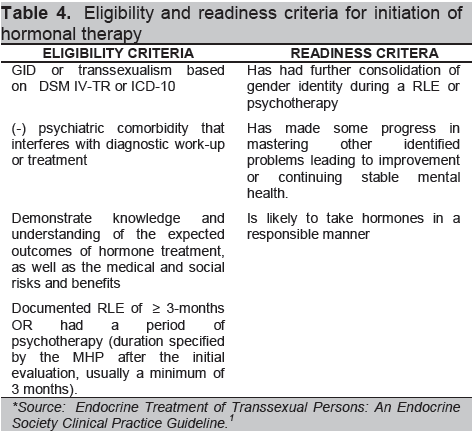

Patients differ in their needs. Some experience relief of dysphoria with psychotherapy or RLE. Others need to proceed to hormone and/or surgical therapy. Should patients consider further treatment, the mental health professional has the responsibility to help patients be psychologically and practically prepared.6 It includes assisting them to make a fully informed decision with clear and realistic expectations, assessing eligibility and readiness. The criteria for eligibility and readiness should be met before referral for further treatment is initiated (Table 4).

Click here to download Table 4

Table 4. Eligibility and readiness criteria for initiation of hormonal therapy

Dr. Busuego (Psychiatrist): When referring to psychiatry, indicate the purpose of the referral. It may be to establish the diagnosis, for psychotherapy or clearance for surgery. Inform the psychiatrist of all prior tests done, medications taken and evidence that the patient is not intersex. There is no specific subspecialty for GID. It can be handled by any general psychiatrist or the subspecialty of consultation liaison (CL) psychiatry. CL deals with medically ill patients who develop psychiatric problems. In the Philippines, there are only 14 CL psychiatrists.

To prepare for psychiatry consult, patients should have an open mind because psychiatrists ask difficult questions about gender and sexuality. Patients will be assessed on their degree of transsexual conviction or their desire to go through sex reassignment including their capacity to compliant with treatment. Psychiatrists assist the patient and their loved-ones in understanding the treatments involved and the decision-making.

One of the functions of a CL psychiatrist is not only to help a medically-ill patient but also to assist a doctor in taking care of a difficult patient. Some doctors may not be comfortable to deal with the management of transsexual patients. One of our rights as physicians is to choose our patients. As such, if a doctor is uncomfortable in dealing with transsexualism, it is a better option to refer to someone else. If you feel you are not treating the patient to the best of your abilities, then you are doing a wrong. Should you wish to treat the patient, yes, part of a CL psychiatrist’s job is to help the referring service or physicians cope with the trials of treating them. We can help you understand and process why you are having problems or why you are uncomfortable.

The goals of hormonal treatment of MTF and FTM transsexuals are similar. The first goal is to reduce endogenous sex hormone levels to subsequently decrease the secondary sex characteristics of the biological sex. The second goal is to replace the endogenous sex hormone with that of the reassigned sex. 1 Hormonal replacement employs the same principle of treatment for hypogonadal patients. The target is to maintain the cross-sex hormone level at the normal physiologic range for the desired gender.1 At present, there are no controlled clinical trials comparing the safety and efficacy of the various treatment regimens.

Before starting MTF hormonal treatment, evaluation of medical conditions that may worsen or arise from hormone depletion and cross-sex hormone treatment should be done. The most important is thromboembolic disease. Others are macroprolactinoma, severe liver dysfunction, breast cancer, coronary artery disease, cerebrovascular disease and severe migraine.1 Absolute contraindications to estrogen therapy are previous venous thrombotic event, history of estrogen-sensitive neoplasm and end-stage chronic liver disease.21 Based on the present history and physical examination of our patient, these conditions are not present.

Baseline biochemical evaluation should be done. Lipid profile and blood sugar should be assessed because hormonal treatment may cause dyslipidemia and hyperglycemia. Prolactin levels, kidney and liver function tests should be determined. If with risk factors, these tests should be done: bone mineral density if at risk for osteoporosis, prostate specific antigen (PSA) if at risk for prostate cancer, hepatitis B & VDRL if high risk for sexually transmitted diseases and complete blood count and coagulation profile if high risk for thromboembolic events.1,22, 23

The patient had normal biochemical markers (Table 2) save for an elevated prolactin which can be attributed to 4 years of estrogen therapy. His estradiol level is within normal range for adult premenopausal females.

Anti-androgens are employed to reduce endogenous testosterone levels. The goal is to suppress testosterone to levels of adult biological women so that estrogen therapy will exert its maximal effect.1 Anti-androgens include spironolactone, cyproterone acetate (CPA) and gonadotropin releasing hormone (GnRH) agonist. Spironolactone acts by reducing 17-alpha hydroxylase to consequently lower testosterone and androstenedione production. It competes with dihydrotestosterone on the androgen receptor. It is contraindicated in renal insufficiency and if serum potassium is >5.5mmol/L. Cyproterone acetate is a synthetic derivative of 17-hydroxyprogesterone and multiple actions to oppose testosterone production and action. It is an androgen receptor antagonist and an alpha-1 reductase inhibitor. It also suppresses follicle stimulating hormone (FSH) and luteinizing hormone (LH) secretion. Lastly, GnRH agonist is employed to disrupt the physiologic pulsatile secretion of FSH and LH at the level of the pituitary. It produces gonadal suppression when blood levels of FSH and LH are continuous.1,24

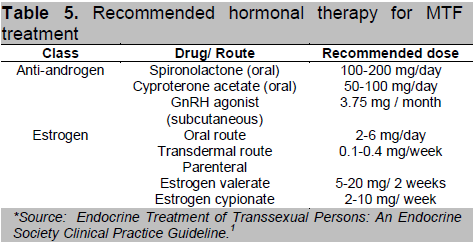

Cross-sex hormone therapy is done with the use of estrogen. Estrogen results in feminizing physical changes such as breast development, decreased testicular volume and muscle mass, redistribution of body fat, softening and decreased oiliness of skin and decreased hair growth. Its metabolic effects includes decreased bone resorption, increased synthesis of hormone binding globulins, increased HDL and triglycerides, enhanced blood coagulation and elevation of blood pressure.24 Estrogen can be given via oral, transdermal and parenteral routes. Serum estradiol should be maintained at the mean daily level for premenopausal women (<200 pg/ml), and the serum testosterone level should be in the female range (<55 ng/dl).1 Table 5 summarizes the recommended dosages of hormonal therapy.

Click here to download Table 5

Table 5. Recommended hormonal therapy for MTF treatment

Decrease in libido and spontaneous erections can be seen as early as 1 to 3 months and maximally at 3 to 6 months upon start of treatment. Redistribution of body fat, decreased muscle mass, softening of skin, decreased oiliness, breast growth and decreased testicular volume can be observed on the 3 rd to 6th month of therapy and maximum at 2 to 3 years. Decreased terminal hair growth occurs at 6 to 12 months and the maximum effect is after 3 years. Onset and maximal effect when it comes to male sexual dysfunction is variable. Likewise, onset of reduction in sperm production is unknown but expected to occur maximally after 3 years. Voice changes are not achieved with hormonal therapy.1

Despite desirable effects of hormone therapy, the Endocrine Society suggests careful observation for adverse outcomes. The most serious is venous thromboembolism. Prolactinoma, breast and prostate cancer, cardiovascular events, osteoporosis and fractures have low evidence of occurrence during the hormonal therapy.1 These risks should be discussed with the patient thoroughly before and during treatment. It is recommended that during the first year, serum testosterone, estradiol and serum potassium be determined every 2-3 months then once to twice yearly thereafter. Depending on the patient’s risk, additional screening should be done for prolactin, cardiovascular disease, breast or prostate cancer and bone mineral density.1

Dr. Michael Villa (Endocrinologist): We have only a few locally available hormonal preparations in the Philippines. For FTM, testosterone undecanoate is available and given as intramuscular injection every 2-3 months. Many patients also acquire testosterone cypionate and proprionate which are purchased from other countries like Taiwan, Malaysia, Singapore and Hongkong.

For MTF, GnRH antagonist but this not locally available. The alternative is a GnRH agonist. The Endocrine Society’s recommendation is 3 mg every month. However, the locally available preparation of GnRH agonist is 11 mg which can be give every 3 months. For cross-sex hormone therapy, a combination pill usually ethinylestradiol 0.035 mg + cyproterone acetate 2 mg is given at a starting dose of 3 tablets daily then gradually increase at 5 to 7 tablets.

Regarding the maximum age at which hormones should be stopped, the rule of thumb is to give it for as long as you can to sustain the sex identity. I have not come across any studies once patients reach 50 or 60 years old. However, current evidence shows that cardiovascular and cancer risk appears to be minimal. Probable pituitary enlargement and osteoporosis was seen in a few but these were not life threatening.

The doses in the Endocrine Society’s recommendations are very high. But for our patient who was taking hormones on his own, he still got the desired effects at suboptimal doses. For the dosages, there are no hard-and-fast guidelines hence the recommendations are always in a range. My dictum is to start low and go slow. Once a level is reached when they are quite comfortable with the achieved changes, they can be maintained on that dose. I believe our Filipino patients may need lower dosages of hormones than our Caucasian counterparts.

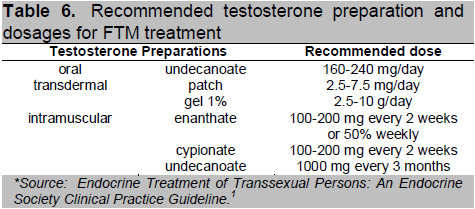

Click here to download Table 6

Table 6. Recommended testosterone preparation and dosages for FTM treatment

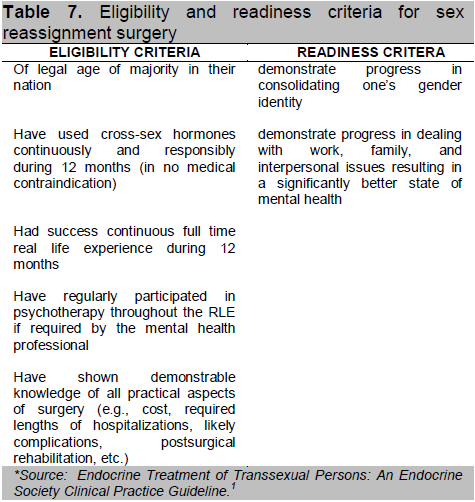

While many transsexuals find comfort with gender expression or hormonal treatment, others deem surgery as indispensable. It provides the desired physical morphology and alleviates psychological discomfort.28 Sex reassignment surgery (SRS) is a group of surgeries wherein the external genitalia and other body structures are refashioned to the opposite gender. The Endocrine Society recommends a set of eligibility and readiness criteria that need to be met (Table 7) prior to surgical planning.1

Click here to download Table 7

Table 7. Eligibility and readiness criteria for sex reassignment surgery

Preoperative hormonal therapy should be interrupted temporarily to avoid thromboembolic complications. Most centers agree to hold oral and IM estrogens and cyproterone acetate one month prior to surgery while transdermal estrogens are stopped for at least a week.1, 18, 29, 30

Cosmetic genital surgery with preservation of neurological sensation is the standard.1 The ultimate goal is the creation of a sensate and aesthetically acceptable vulva, reconstruction of urethra, creation of a stable and sensate neovagina with adequate dimensions, elimination of erectile tissue to avoid narrowing of the introitus and protrusion of the urethral meatus/clitoris, and preservation of orgasmic capability.29

Sex reassignment surgery is a staged process. Vaginoplasty is performed in a single or multiple operative setting. Orchiectomy is done with preservation of the scrotal skin should vaginoplasty or labiaplasty be desired. Partial resection of the penis is then done. The neovagina is created by inverting the penile skin. The urethra is shortened and direction of the urinary stream is diverted downward to allow urination while sitting. The neoclitoris is fashioned using the preserved dorsal portion of the glans with attachments to its neurovascular bundle.31 The labia majora is created using scrotal skin and the labia minora is constructed from the prepuce or penile skin.29,32 A prosthesis will be placed in the neovagina after surgery to maintain its dimensions. The amount of time the prosthesis is removed from the neovagina will be gradually increased over the next 8 weeks. 29,33

Continued administration of cross-sex hormones is required to avoid symptoms and signs of hormone deficiency and maintain feminine physical characteristics. Some experts recommend resumption of hormones a week after surgery or once physical recovery is sufficient. 18,32 Most centers advocate lowering estrogen to half of the preoperative dose since no endogenous testosterone is available to oppose estrogen. Others recommend the full transdermal dose for 1 month or continuing the same dose after surgery.18,30, 34-36

Other feminizing procedures may be done as requested by the patient. This includes breast augmentation, body contouring, facial feminizing surgeries, chondroplasty and voice changes surgery and laser for unwanted hair. 29,37,38

In the genital region, the most common surgical complications were stricture in the vaginal introitus, resection of corpora, vaginal stricture and loss of vaginal depth. In the urinary system, the most common complications are obstructive voiding disorder, stricture recurrence and dribbling. Rectal injury was the most common among the gastrointestinal events. There were only minor wound healing disorders and cases of blood transfusion.39

In general, most transsexuals reported improvement in sex life such as more satisfactory orgasm and increased vaginal secretion during sexual intercourse. 40 Persistent regret, viewed as the worst outcome of SRS, is very low at only 1-1.5%.29,41,42

Dr. Jaime Jorge, Jr. (Surgeon): We require several things from co-managing services prior to SRS. From psychiatry, we need the diagnosis of GID, psychiatric comorbidities and clearance for surgery. From the medical team, we need general medical clearance as with any surgery. We need to determine the probability of hypercoagulability and sexually transmitted diseases.

In our local experience, patients we receive commonly self-medicate with hormones even before psychiatry or surgical consult. In our center, we only do MTF SRS. Usually, patients undergo secondary feminizing surgeries like breast augmentation or thyroid cartilage trimming before they contemplate genital surgery. This is primarily for financial reasons. Patients who underwent surgery usually complete psychiatry consult and hormone therapy prior to surgery.

Literature review shows no clear evidence that the aforementioned interventions cure or alleviate gender dysphoria, in the absence of randomized controlled trials. Trials would admittedly be difficult to conduct given the nature of the intervention. Opinions are gleaned from numerous published observational studies. A meta-analysis which compiled 28 cross-sectional studies and cumulatively observed 1833 patients reported large improvements in dysphoria (80% of patients), psychiatric symptoms (78%), quality of life (80%) and sexual functioning (72%) after sex reassignment. However, there was significant heterogeneity due to different methods and measures of outcome. This study concluded that current data suggest sex reassignment to likely improves gender dysphoria and quality of life but evidence is of low quality due to the study designs, heterogeneity and high chance of bias.45

No Philippine data is published. The authors contacted five transsexual organizations and conducted an online survey. Nineteen individuals responded. The mean age of patients was at 29 years old (range 22-40) and majority was MTF at 89%. Majority (76.5%) was taking multiple hormones. Majority (94%) felt that their treatment is effective and they were satisfied or very satisfied (76.5%) with the changes in their body. The reasons mentioned for this satisfaction include a good mental, emotional and physical well-being as well as desirable and more comfortable physical appearance.

Dr. Laura Trajano-Acampado (Endocrinologist): In the Philippines, I think one of the issues in the management of transsexuals is if physicians will treat or not. Because of our sociocultural and religious background, some doctors may hesitate to treat. But if we don’t, patients will use the underground medical management. At some point in time, they probably approached us but we did not know how to handle them. Some may have also asked, “Is it ethical to encourage them?” But at the end of the day, if we just close our eyes, turn our backs and not treat them, they will probably go to the “doctor” who is their neighbor or their friend. That is why this is a very important issue.

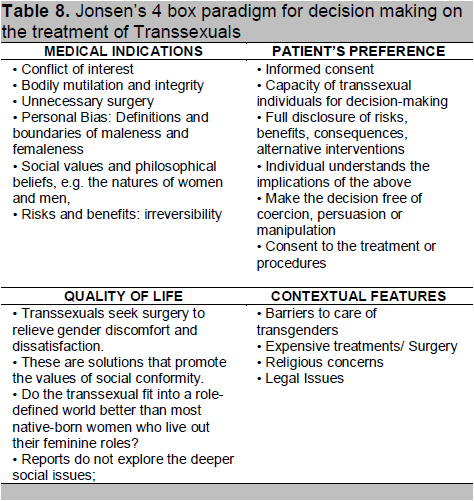

Dr. Marita V. Tolentino (Bioethics expert): I would like to share with you Dr. Jonsen's 4 box approach in ethical analysis. 46 There are 4 important aspects of a case that need to be examined to identify bioethical issues (Table 8). The analysis of the case should follow this order.

The first box is about medical indications. One's expertise, training, research and understanding should lead one to decide what is best for a patient using the principles of beneficence and non-maleficence. To apply these principles, we refer to the goals of medicine. These include the following: (1) promote health and prevent disease, (2) relieve pain and suffering, (3) cure if possible, (4) prevent untimely death, (5) restore function and bring back autonomy, (6) counsel and advise regarding health and (7) avoid harm. We should achieve more than one of these goals. We also check for conflicts of interest. Next, we determine the necessity for such treatments. Also, doctors must check their own personal biases, social values and philosophical beliefs regarding gender as these may be in conflict with the patient’s. Finally, consider the risks and benefits of treatment.

Click here to download Table 8

Table 8. Jonsen’s 4 box paradigm for decision making on the treatment of Transsexuals

The second box is preference of the patient, which applies the principle of respect for persons. Validity of informed consent must be ascertained. Due to psychiatric comorbidities such as depression, some transsexuals may not have a full capacity for decision-making. This must be cleared with the mental health professional. Full disclosure of risks, benefits, consequences and alternative interventions must be done. To ensure that the patient understands the implications of treatment, several meetings may be needed. The patient’s decision must be free of coercion, persuasion or manipulation. To ascertain this, the psychiatrist may request to speak with the patient separately from the family or friends. Lastly, a formal consent should be obtained for the procedure.

The third box is quality of life of the patient before, during and after medical intervention through different point of views – the practitioner, patient, family and society. Transsexuals say they seek surgery to relieve gender discomfort and dissatisfaction. Because society has a vision of masculinity or femininity, it one feels differently, one must change to conform to what society dictates. But after the change, will the transsexual fit into the society in the same way that a natural-born women does? If the answer is yes, what kind of life is this and is it really satisfactory?

The fourth box is a contextual feature. In the medical system, barriers to care of transsexuals may exist. This includes biases or awkwardness for medical professionals, religious and legal concerns. Treatments are also expensive. Decisions for treatment must consider justice, economics, religion, law and institutional policies.

Once you have identified ethical issues, how do you resolve them? First, clarify the facts of the case. Why and what is it they are experiencing in their body? What if the environment is changed? Second, manage potential and actual conflicts of interest. Third, using Jonsen’s boxes, highlight the principle that is most applicable and make this the overriding principle in your decision. Then make ways to minimize the unacceptable issues. Fourth, ensure the real participation of the patient and his/her significant others in decision-making.

To help physicians decide on the course of action in the treatment of transsexual individuals, several lenses can be employed. The first lens is the medical lens, which concerns the diagnosis and disease perspective. But many say we should start using a social lens or the gender lens. It is really the environment and the society-- our attitude towards transsexuals that should change. Because of societal constraints of masculine and feminine role-defined behavior, transsexuals do not fit and become uncomfortable. Thirdly, we use the bioethical lens, which highlights the principles of respect for persons, beneficence, non-maleficence and justice. In here, balancing of risks and benefits is an important feature.

JG Raymond 1980 (Raymond) 47 raised some questions which are interesting. She asks – does feeling trapped in the wrong body and desiring to be the other sex qualify as a disease? What about being trapped in the wrong skin, or in the wrong period of time or the wrong social economics? Do we label it now as “transdermatologic”, “transchronologic” or“transeconomical?” She raised concern on medicalizing social issues. She does not accept the notion that according to the transsexuals and defenders of surgery, “Biology is destiny!” -- that it is impossible to change male or female behavior, traits and characteristics unless one also changes one’s body. And that the body is all-important, it guides destiny and that all else is body-bound.

Here are now the challenges to Filipino transsexual advocates. We should start studying the cultural dimensions of masculinity and femininity among Filipinos. What would be the Filipino medical and psychiatric definitions of masculinity and femininity? We need data on the risks of hormonal and surgical interventions locally. We need data on the quality of life of Filipino transsexuals who have undergone hormonal and surgical interventions to include identifying which part of the treatment provides them satisfaction.

From the foregoing clinical case presentation and discussion, the authors outline several learning points:

· Transsexualism, is a phenomenon currently classified as a medical condition in ICD-10 and termed Gender Identity Disorder (GID) in the field of psychiatry. The proposed treatment is sex reassignment. Several international guidelines exist to guide clinicians in the treatment of transsexuals.

· Sex reassignment involves a multidisciplinary approach. Proper diagnosis, evaluation and treatment by the psychiatrist are required before proceeding with further medical and surgical interventions. The patient’s valid informed consent with full disclosure and understanding of the risks and benefits of treatment must be secured as well.

· Hormonal therapy follows the principles of suppression of endogenous hormones and cross-sex hormone replacement.

· Surgical interventions are multi-staged and include genital reconstruction and ancillary procedures such as surgeries in the breast, face and other body parts to attain the physical morphology of the desired sex.

· In some countries, legal barriers exist in making the full transformation of transsexuals. Some ethical issues may also arise in their treatment.

1. Hembree WC, Cohen-Kettenis P, Delemarre-van de Waal HA, Gooren LJ, Meyer III WJ, et al. Endocrine treatment of transsexual persons: An Endocrine Society Clinical Practice Guideline. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2009, 94(9):3132–3154

2. American Psychological Association, Task Force on Gender Identity and Gender Variance. (2009). Report of the Task Force on Gender Identity and Gender Variance. www.apa.org/pi/lgbc/transgender/ 2008TaskForceReport.html. Accessed February 1, 2013.

3. American Psychiatric Association : Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, Fifth edition. Arlington, VA, American Psychiatric Association, 2013.

4. IOM (Institute of Medicine). 2011. The health of lesbian, gay, bisexual and transgender people: Building a foundation for better understanding. Washington, DC: The National Academies Press.

5. International Classification of Diseases – 10. World Health Organization. http://www.who.int/classifications/icd/en/. Accessed February 1, 2013

6. The World Professional Association for Transgender Health. Standards of Care for the Health of Transsexual,Transgender, and Gender Nonconforming People, 7th edition (2011). www.wpath.org. Accessed January 15, 2013

7. Bakker A,Van Kesteren PJ,Gooren LJ, Bezemer PD. The prevalence of transsexualism in The Netherlands. Acta Psychiatr Scand. 1993 Apr;87(4):237-8.

8. Wilson P,Sharp C, Carr S. The prevalence of gender dysphoria in Scotland: A primary care study. Br J Gen Pract. 1999 December; 49(449): 991–992.

9. De Cuypere G,Van Hemelrijck M,Michel A,Carael B,Heylens G, Rubens R, et al. Prevalence and demography of transsexualism in Belgium. Eur Psychiatry. 2007 Apr;22(3):137-41.

10. Gooren L, Van Kesteren P, Megens J. Epidemiological Data on 1194 Transsexuals. Poster presented on the conference "Psychomedical Aspects of Gender Problems", Amsterdam, April 18 - 20, 1993.

11. Weitze C, Osburg S; “ Transsexualism in Germany: Empirical data on epidemiology and application of the German Transsexuals’ Act during its first ten years .“ Archives of Sexual Behavior. 1996; 25 (4): 409-425.

12. Tsoi WF. The prevalence of transsexualism in Singapore. Acta Psychiat Scand. 1988; 78 (4): 501-504.

13. Castagnoli C. Transgender Persons’ Rights in the EU Member States 2010. Directorate –General for Internal Policies. Policy Department Citizens’ Rights and Constitutional Affairs. www.ipolnet.ep.parl .union.eu/ipolnet/cms. Accessed February 10, 2013.

14. www.transgenderlaw.org, Accessed February 10, 2013.

15. Godwin J. Legal environments, human rights and HIV responses among men who have sex with men and transgender people in Asia and the Pacific: An agenda for action. UNDP 2010. www.asiapacificforum.net. Accessed February 13, 2013.

16. Republic Act No. 9048 An Act Authorizing The City Or Municipal Civil Registrar Or The Consul General To Correct A Clerical Or Typographical Error In An Entry And/Or Change Of First Name Or Nickname In The Civil Register Without Need Of A Judicial Order, Amending For This Purpose Articles 376 And 412 Of The Civil Code Of The Philippines. March 22, 2001. www.Lawphil.Net/ Statutes/Repacts/Ra2001/ Ra_9048_2001. Accessed February 13, 2013.

17. Republic Act No. 10172, An Act Further Authorizing The City Or Municipal Civil Registrar Or The Consul General To Correct Clerical Or Typographical Errors In The Day And Month In The Date Of Birth Or Sex Of A Person Appearing In The Civil Register Without Need Of A Judicial Order, Amending For This Purpose Republic Act Numbered Ninety Forty-Eight. Http://Www.Gov.Ph/2012/ 08/15/Republic-Act-No-10172/. Accessed February 13, 2013.

18. Godano A, Maggi M, Jannini D, Meriggiola MC, Ghigo E, Todarello O, et al. SIAMS-ONIG Consensus on hormonal treatment in gender identity disorders. J. Endocrinol. Invest. 2009; 32:857-864.

19. Cole CM,O'Boyle M,Emory LE, Meyer WJ. 3rd. Comorbidity of gender dysphoria and other major psychiatric diagnoses. Arch Sex Behav. 1997 Feb;26(1):13-26.

20. Hepp U,Kraemer B,Schnyder U,Miller N, Delsignore A. Psychiatric comorbidity in gender identity disorder. J Psychosom Res. 2005 Mar; 58(3):259-61.

21. Coleman E, Bockting W, Botzer M, Cohen-Kettenis P, DeCuypere. Standards of Care for the Health of Transsexual, Transgender and Gender-Nonconforming People, Version 7. International Journal of Transgenderism. 2011; 13:165–232.

22. Dahl M, Feldman JL, Goldberg J, Jaberi A, Bockting W, Knudson G. Endocrine Therapy for Transgender Adults in British Columbia Suggested Guidelines. 2006. www.vch.ca/transhealth. Accessed February 1, 2013

23. Moore E, Wisniewski, Dobs A. Endocrine Treatment of Transsexual People: A Review of Treatment Regimens, Outcomes, and Adverse Effects. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. August 2003; 88(8):3467–3473.

24. Katzung B. Basic and Clinical Pharmacology 10th Edition. McGraw Hill, 2006.

25. Gooren, L. J.G. and Giltay, E. J. (2008), Review of Studies of Androgen Treatment of Female-to-Male Transsexuals: Effects and Risks of Administration of Androgens to Females. Journal of Sexual Medicine. 2008; 5: 765–776.

26. Nieschlag E,Behre HM,Bouchard P,Corrales JJ,Jones TH,Stalla GK,Webb SM, Wu FC. Testosterone replacement therapy: Current trends and future directions. Hum Reprod Update. 2004 Sep-Oct;10(5):409-19.

27. Asscheman H,Giltay EJ,Megens JA,de Ronde WP,van Trotsenburg MA, Gooren LJ. A long-term follow-up study of mortality in transsexuals receiving treatment with cross-sex hormones. Eur J Endocrinol. 2011 Apr;164(4):635-42.

28. Hage, JJ, Karim, RB. Treatment options for nontranssexual gender dysphoria. Plastic and Reconstructive Surgery. 2000; 105(3), 1222–1227.

29. Bowman C & Goldberg J. Care of patient undergoing SRS. Trans Care Project 2006. http://www.vch.ca/transhealth.Accessed February 1, 2013.

30. Futterweit W. Endocrine therapy of transsexualism and potential complications of long-term treatment. Arch Sex Behav. 1998, 27:209–26.

31. Jones HW. Transsexualism and Sex Reassignment, Richard Green, M.D. and John Money, Ph.D., Editors; Chapter 22; Johns-Hopkins Press, 1969.

32. Amend B,Seibold J,Toomey P,Stenzl A, Sievert KD. Surgical Reconstruction for Male-to-Female Sex Reassignment. Eur Urol. 2013 Jan 5. pii: S0302-2838(12)01560-6.

33. Tugnet N, Goddard JC, Vickery RM, Khoosal D, Terry TR. Current management of male-to-female gender identity disorder in the UK. Postgrad Med J. 2007;83:638–642.

34. Gooren LJ. Care of transsexual persons. N Engl J Med. 2011;364:1251-7.

35. Van Kesteren P, Lips P, Gooren LJG, Asscheman H, Megens J. Long-term follow-up of bone mineral density and bone metabolism in transsexuals treated with cross-sex hormones. Clin Endocrinol (Oxf), 1998; 47:337–342.

36. Michel A, Mormont C, Legros J. A psycho-endocrinological overview of transsexualism. Eur J Endocrinol. 2001; 145:365–376.

37. Becking AG, Tuinzing DB, Hage JJ, Gooren LJG. Transgender Feminization of the Facial Skeleton. Clinics in Plastic Surgery. 2007, 34(3): 557-564.

38. Cregten-Escobar P,Bouman MB,Buncamper ME, Mullender MG. Subcutaneous mastectomy in female-to-male transsexuals: a retrospective cohort-analysis of 202 patients. J Sex Med. 2012 Dec;9(12):3148-53.

39. Neto RR, Hintz F, Krege S, Rubben H, Vom Dorp F. Gender reassignment surgery - a 13 year review of surgical outcomes. Int Braz J urol. 2012; 38 (1): 97-107.

40. De Cuypere G, T’Sjoen G, Beerten R, Selvaggi G, De Sutter P, et al. Sexual and Physical Health after Sex Reassignment Surgery. Archives of Sexual Behavior, December 2005; 34 (6) : 679–690.

41. Pfa ̈fflin, F. & Junge, A.(1998).Sex reassignment. Thirty years of international follow-up studies after sex reassignment surgery: A comprehensive review, 1961–1991. Düsseldorf, Germany : Symposion, 2003.

42. Lawrence, AA. Factors associated with satisfaction or regret following male-to-female sex reassignment surgery. Archives of Sexual Behavior. 2003; 32: 299–315.

43. Selvaggi G, Elander A. Penile reconstruction/formation. Curr Opin Urol. 2008 Nov;18(6):589-97.

44. Wierckx K,Van Caenegem E,Elaut E,Dedecker D, Van de Peer F, et al. Quality of life and sexual health after sex reassignment surgery in transsexual men. J Sex Med. 2011 Dec;8(12):3379-88.

45. Murad MH, Elamin MB, Garcia MZ, Mullan RJ, Murad A, Erwin PJ, Montori VM. Hormonal therapy and sex reassignment: A systematic review and meta-analysis of quality of life and psychosocial outcomes. Clinical Endocrinology (2010) 72, 214–231.

46. Jonsen AR, Siegler M, Winslade WJ. Clinical Ethics: A practical approach to ethical decisions in clinical medicine, 3rd Edition McGraw-Hill, Inc. Health Professions Division, New York 1992.

47. Raymond JG, Technology on the Social and Ethical Aspects of Transsexual Surgery, Susan's Place Transgender Resources, June 1980.