Many international guidelines on research ethics have been developed to guide countries and institutions on the proper conduct of biomedical research and to protect the dignity, safety and rights of human research participants. The most frequently mentioned is the

Declaration of Helsinki

by the World Medical Association (WMA), with its latest revision in 2008. 1

Other sources of guidance include the

International Ethical Guidelines for Biomedical Research Involving Human Subjects

by the Council for International Organizations of Medical Sciences (CIOMS), which outlines the application of the Helsinki Declaration in developing countries; and

Guidelines for Good Clinical Practice (GCP) for Trials on Pharmaceutical Products

of the World Health Organization (WHO) (1995) and the International Conference on Harmonisation (ICH)

Guideline for Good Clinical Practice

(1996), both of which set the standards for the conduct of clinical trials.2-4

On the other hand, the United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization (UNESCO) adopted the

Universal Declaration on Bioethics and Human Rights

in 2005 to assist member states in the formulation of national legislation, regulations and policies. 5

The report by the Nuffield Council on Bioethics,

The Ethics of Research Related to Healthcare in Developing Countries

(2002, followed up in 2005), is also frequently referred to by researchers and ethics review committees in many countries. 6

Recently the World Health Organization released a new set of guidelines for ethical review of research,

Ethics Review Standards and Operational Guidance for Ethics Review of Health-Related Research with Human Participants. World Health Organization 2011.

In light of the many developments in health research (e.g., genomics, biobanking, drug and vaccine development, and discovery of natural products) and the current globalization of biomedical research activities, it is important to appreciate the efforts being made for protection of human participants in research in our region.7

The aim of this paper is to review the ethical challenges in health research encountered in Asia and to describe the regional efforts to address them. The Philippine human protection system is presented as a specific example of a national initiative towards ethical health research. Most of the perceptions and opinions expressed in the article are results of the author's participation in some of the activities of the Forum for Ethical Review Committees in Asia and the Western Pacific Region (FERCAP), and her involvement as chair of the National Ethics Committee and co-chair of the Philippine Health Research Ethics Board in the past years.

Issues and challenges

The Helsinki Declaration and the other aforementioned international guidelines expressly require that all biomedical researches involving human participants undergo ethical review prior to implementation. The ethical review is carried out by an ethics review committee (with appropriate expertise and a sufficiently diverse membership) that works independently of the researcher and the sponsor. The committee looks into the following concerns in the study:

1. Scientific soundness of the protocol including an imperative for human participation

2. Relevance of the study to local or national health needs

3. Vulnerability of the study population

4. Adequacy of the informed consent process

5. Equity of selection of participants and appropriateness of the inclusion/exclusion criteria

6. Protection of the privacy of the participants

7. Favorable benefit/risk ratio

8. Minimization of harm

9. Control arm and standard of care

10. Appropriateness of the investigator's expertise

11. Adequacy of facilities at the study site

Items 2, 3 and 9 are of particular interest in developing countries.

Speakers in various fora have noted a large variation in the abilities of developing countries to carry out an effective and adequate ethical review of health researches.8-10 Reasons often cited are:

1. Non-existent health data systems

2. Difficulty in recruiting qualified committee members

3. Lack of ethics review training programs

4. Absence of a quality assurance system in ethical review

5. Administrative support is lacking

These deficiencies result in delays in the review process, post-review communications and inconsistency in ethical review decisions. These subsequently cause delay in the implementation of the study, loss of credibility of the ethics review committee and diminution of support in the ethics review process.

For example, to ensure that a study is not exploitative of the community, the ethics review committee will assess whether the research addresses a significant national or local health problem. Evidence to support relevance is usually in the form of reliable epidemiologic data. Unfortunately these data are not always available. Corollary to the issue of relevance is the community's post-study accessibility to the treatment that is proven effective. Pharmaceutical companies hedge the question of cost (as a determinant of accessibility) of a drug or vaccine by explaining that the cost can only be determined by the size of the market and the overall investment in its development. These can only be computed after all the required trials for drug registration are done. This reasoning is a nudge to the ethics committee to approve the drug trial so that the clinical trials can be done and all the marketing factors can be quickly determined.

Pervasive poverty in many Asian countries and the absence of universal health care programs bring about lack of access to medical treatment. This creates a situation in which clinical trials become the default means whereby patients get attention and care. Therapeutic misconception and the inability of the participants to distinguish research from clinical treatment make the informed consent process difficult to acquire.

Teck-Chuan Voo et al highlighted the issue of access to standard care by patients participating in medical studies based on the Declaration of Helsinki, which stipulated that in “every medical study, every patient—including those of a control group, if any—should be assured of the best proven diagnostic and therapeutic method.”11 The authors considered whether “the provision of care for control groups adhere to a universal standard—the best current treatment worldwide, or at least an established and effective intervention? Should it be the local de facto standard—the actual health care practices of the host country? Or should it perhaps adhere to the local de jure standard, reflecting the judgments of medical experts in the host community on the most effective treatment and care practices for that community?” When international guidelines are not clear, the local ethics review committee will be very much dependent on a consensus of its inexperienced members.

A fundamental principle of research ethics is that the consent of the potential research participant must be voluntary and shall be based on sufficient knowledge and understanding of the procedures, risks and benefits involved. Conceptually difficult topics like genetics/genomics and the necessary translation of complex research procedures in the local language present challenges in the informed consent process. Frequently, the literal translation of the informed consent form into a dialect fails to capture the nuances of scientific jargon and those of a foreign language. Additionally, there are social and cultural norms—like permission from the spouse (usually the male), family or community—which are traditionally sought in many Asian countries, that are not sufficiently considered in the international guidelines.

Regional and international conferences

In the past decade, Asia has hosted many international and regional conferences that have provided opportunities to raise awareness on the ethical challenges in health researches in the region. The following are some examples of these conferences.

The World Commission on the Ethics of Scientific Knowledge and Technology (COMEST, taken from the French name Commission mondiale d’éthique des connaissances scientifiques et des technologies) was held in Bangkok, Thailand on March 23 - 25, 2005 and in Kuala Lumpur, Malaysia on June 16 - 19, 2009. COMEST is an advisory body and forum of reflection that was set up by UNESCO in 1998. Chaired by Mr. Alain Pompidou, the Commission is composed of eighteen leading scholars from scientific, legal, philosophical, cultural and political disciplines from various regions of the world, appointed by the UNESCO Director-General in their individual capacity; along with eleven ex officio members representing UNESCO's international science programs and global science communities. The Commission is mandated to formulate ethical principles that could provide decision-makers with criteria that extend beyond purely economic considerations. Currently, COMEST is working in several areas: environmental ethics, with reference to climate change, biodiversity, water and disaster prevention; the ethics of nanotechnologies, along with related new and emerging issues in converging technologies; ethical issues relating to the technologies of the information society; science ethics; and gender issues in ethics of science and technology.

The 12th Asian Bioethics Conference was organized by the Asian Bioethics Association (ABA) in Taipei, Taiwan in September 2011. A special workshop on clinical research ethics featured ethical issues in stem cell research, biobanking, research on rare diseases, surrogacy of informed consent, and pricing of drugs. Organized in 1998, the basic objective of the ABA is to promote scientific research in bioethics in Asia through open and international exchanges of ideas among those working in bioethics in various fields of study and in different regions of the world. To this end, the ABA seeks to organize and support international conferences in bioethics in Asia and to assist in the development and linkage of regional organizations for bioethics. It also encourages other academic and educational work or projects to accomplish their goals consistent with the objectives of the Association. URL: http://www.aprec-nhg.com.sg/

The Asia Pacific Research Ethics Conference (APREC) brings together the regions' Institution Review Boards (IRBs), ethics committees, research and academic institutions, top national health authorities and the pharmaceutical industry in a program focusing on human subject protection. The 2nd APREC Conference held in Singapore on March 8 - 9, 2012 featured the following keynote lectures: “The Systematic Assessment of Research Risks: Does it Depend upon Culture or Context?” by Dr. Ezekiel J. Emmanuel; “Research Ethics Poser: Where is the Truth in the Sea of Information?” by Prof. Toshiaki A. Furukawa; “Research Ethics Falling Behind Globalization of Clinical Research” by Dr. Johan P. E. Karlberg; and “The Proliferation of Biobanks— Ethical Opportunity or Ethical Nightmare?” by Prof. Alastair V. Campbell.

Other initiatives

Regional and individual country strategies that address the ethical challenges in health researches in Asia have been varied. These include the conduct of regional conferences, development of regional and national research ethics training courses (masters courses and intensive courses in both campus-based and distance learning modes), establishment of quality assurance systems, development of national GCP guidelines and the establishment of health research databases.12,13

The Forum for Ethical Review Committees in the Asian and Western Pacific Region was formed in Bangkok, Thailand on January 12, 2000 by a group of bioethicists and medical experts as a project of the World Health Organization (WHO) Special Training and Research Programme in Tropical Diseases (TDR). FERCAP is a regional forum under the umbrella of the Strategic Initiative for Developing Capacity in Ethical Review (SIDCER). The objective was to foster improved understanding and better implementation of ethical review of behavioral and biomedical researches in the region. Its major projects involve capacity building and education for research ethics committees in Asia, and developing models of good research ethics review in Asia and the Western Pacific. These programs include the organization of annual international conferences, training programs (courses on human participant protection, standard operating procedure (SOP) development and surveying and evaluating ethical review practices), and networking [SIDCER; WHO-TDR; WHO South-East Asia Regional Office (SEARO); WHO Western Pacific Regional Office (WPRO); WHO-TDR Clinical Coordination and Training Center (CCTC); and other national, regional, and international institutions]. FERCAP is affiliated with and holds office at the Faculty of Allied Health Sciences , Thammasat University.

The 11th FERCAP International Conference was held in Daegu, South Korea on November 20 - 23, 2011, with the theme, “Innovation, Integration and Ethical Health Research.” Dr. Greg Koski gave the keynote address which focused on “Building a Global Network in clinical Health Research in Support of Innovation and Integration.” Session topics included discussions on describing the environment for innovation and integration towards ethical health research, strengthening regulatory compliance in ethical health research, dealing with innovation/developments in ethical health research, improving national ethical review systems, social and community issues in ethical health research, addressing issues in different types of ethical review, areas for capacity building of ethics review committees, and addressing IRB issues at various levels.

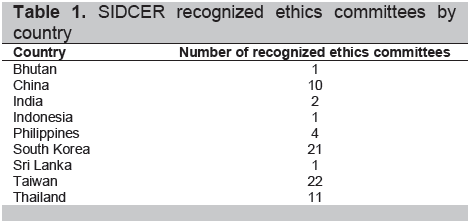

FERCAP is also involved with the SIDCER Recognition Program for Ethics Committees. Under the WHO, the SIDCER was created as a network of independently established regional fora for ethics committees in five regions of the world. The regional fora consist of the Forum for Ethics Committees in the Confederation of Independent States (FECCIS), Forum for Ethics Committees in Asia & the Western Pacific (FERCAP), the Foro Latino Americano de Comités de Ética en Investigacion en Salud (Latin American Forum of Ethics Committees in Health Research, FLACEIS), the Forum for Institutional Review Boards/Ethics Review Boards (ERBs) in Canada and the United States (FOCUS), and the Pan African Bioethics Initiative (PABIN). The SIDCER recognition program provides an assurance to the public that the ethics committee protects research subjects from harm and exploitation and preserves their rights through validation of compliance with established international and national standards. Hamadian and Johansen reported the recognition of 73 ethics committees in Asia (Table 1).14

Click here to download Table 1

Table 1. SIDCER recognized ethics committees by country

Summary of country initiatives in research ethics

In a presentation at the Comparative International Workshop on the Regulation and Organization of Research Ethics Review at the Faculty of Law, University of Toronto on June 16 to 18, 2005, Dr. Cristina Torres, Regional Coordinator of FERCAP, described a general trend towards centralization of research ethics review in Asia. Both Thailand and the Philippines have developed national guidelines for ethical review of biomedical researches and for special types of health research. Thailand has made special provisions for HIV/AIDS studies. On the other hand, the Philippines has developed specific guidelines for researches in organ transplantation, genetic engineering, HIV/AIDS, and assisted reproductive technology. Other countries like Malaysia and Singapore have developed their own version of GCP to guide ethical review. These national guidelines generally followed the major international research ethics guidelines. She noted that in some parts of Asia, community involvement in assessing research ethics review structures is becoming increasingly common. Community involvement often stems from community initiatives to become active participants. In Thailand, for example, an HIV study group has created a community advisory board that liaise with the host community to deal with research ethics review issues.15

Countries like Indonesia, Malaysia, Cambodia, Vietnam, Laos and the Philippines have established national ethics committees that review biomedical researches. Dr. Torres pointed out that as with many other jurisdictions, the problem of enforcement remains. Research ethics guidelines do not have legal authority, only moral force.

Philippine initiatives in health research ethics

In 1984, the Philippine Council for Health Research and Development under the Department of Science and Technology (DOST) created the National Ethics Committee (NEC), which was tasked to ensure that health researches in the Philippines adhered to international ethical guidelines. The following year, the committee formulated the National Guidelines for Biomedical Research. The latest edition, the 2011 National Ethical Guidelines for Health Research, was released on 16 March 2012.16

On March 17, 2003, key agencies of government—the DOST, the Department of Health (DOH), the Commission on Higher Education (CHED), and subsequently the University of the Philippines Manila - National Institutes of Health (UPM-NIH)—signed a memorandum of understanding that established the Philippine National Health Research System (PNHRS). The PNHRS shall promote and enhance cooperation and sharing of resources, and the development of the capacity for knowledge production, use, management, research and financing.

The PNHRS envisions a vibrant, dynamic and responsible health research community for the attainment of national and global health goals. One of its strategic goals is the development of high-performing and ethical research organizations. To see to the attainment of this goal, the Philippine Health Research Ethics Board (PHREB) was created through DOST Special Order 091 s. 2006 as the national policy-making body on health research. The PHREB shall formulate guidelines for ethical conduct in health research, and establish and manage ethics review committees (ERCs). It was also mandated to monitor the performance of ERCs, and to provide advice to the PNHRS Governing Council and to other appropriate entities (including the Food and Drug Administration) related to ethical issues in human health research.

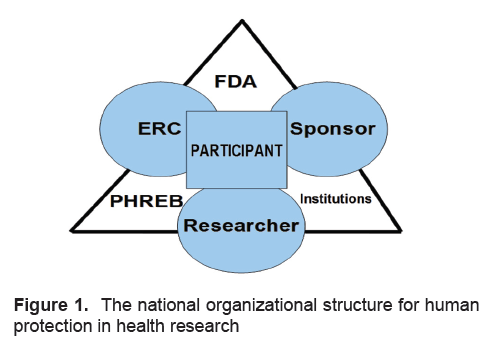

Structurally, the PHREB became one of the 3 regulatory bodies on human protection in research; the others being the Food and Drug Administration and research institutions themselves (Figure 1). The second level of control in human protection lies on the researcher, the sponsor and the ethics review committee. At the center, representing the first level of protection, is the research participant/patient.

In the past 5 years, the PHREB accomplished several important actions that made an impact health research ethics. Among these are:

1. The development of a set of policies and standards for registration and accreditation of Ethics Review Committees

2. The establishment of the National Database of Ethics Review Committees, which now number more than 200 nationwide

3. The maintenance of the roster of individuals with formal degrees or who have attended short courses in research ethics

4. The organization of a Research Ethics Training group, composed of the UPM-NIH, the University of the Philippines Bioethics Group, the Southeast Asia Bioethics Organization, the University of Santo Tomas Bioethics Group and the PHREB Sub-Committee on Training, which has agreed on a common research ethics training curriculum.

Click here to download Figure 1

Figure 1. The national organizational structure for human protection in health research

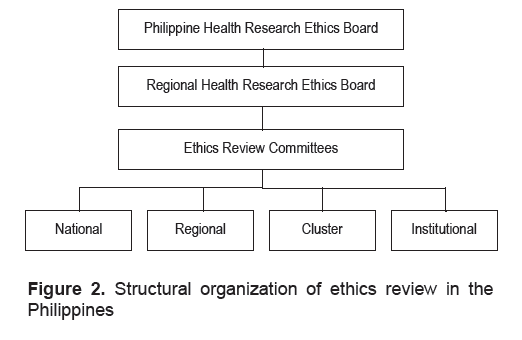

Structurally, ethics review in the Philippines is decentralized (Figure 2). Ethics review is supervised by the PHREB and its regional arms, the Regional

Health Research Ethics Boards. Aside from institutional ethics review committees, regional ethics review committees and cluster review committees conduct

ethics review for researches in institutions without their own ethics review systems.16

Click here to download Figure 2

Figure 2. Structural organization of ethics review in the Philippines

At present, there are 8 regional review committees that function as a consortium of institutions in various regions, while 2 institutional review committees—De La Salle University and the UPM-NIH—are responsible for performing ethics review for Region IV-A and the National Capital Region, respectively. To date, there are 103 registered ERCs in the Philippines.

Through the recently implemented accreditation system, the PHREB grants 3 levels of accreditation, based on the following criteria:

1. Functionality of the structure and membership of the ERC

2. Adequacy of SOPs and consistency in implementation

3. Adherence to international, national and institutional guidelines and policies

4. Completeness of the review process

5. Adequacy of after-review procedures

6. Adequacy of administrative support for ERC activities

7. Efficient and systematic recording and archiving.

ERCs in level 3 that have complied with all 7 criteria are authorized to do ethics review of clinical trials for registration of new drugs. Level 2 ERCs that have complied with the first 6 criteria are authorized to review clinical trials which are not for drug registration. Level 1 ERCs that have complied with the first 5 criteria are authorized to review other health researches aside from clinical trials.

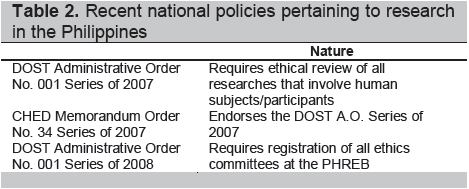

Some recent national policies regarding research are presented in Table 2.

Click here to download Table2

Table 2. Recent national policies pertaining to research in the Philippines

Capacity-building in health research ethics is robust in Asia. There are international, regional and national efforts to respond to the challenge of ensuring that health research is conceptualized and conducted in a manner that is protective of the dignity and respectful of the rights of human participants.

1. World Medical Association Declaration of Helsinki: Ethical principles for medical research involving human subjects. Seoul: 59th WMA General Assembly, 2008. http://www.wma.net/e/policy/b3.htm (January 15, 2009).

2. Council for International Organizations of Medical Sciences (CIOMS) in collaboration with the World Health Organization (WHO). International guidelines for biomedical research involving human subjects. Geneva: World Health Organization, 2002. http://www.cioms.ch/publications/layout_guide2002.pdf.

3. World Health Organization. Guidelines for good clinical practice (GCP) for trials on pharmaceutical products. WHO Technical Report Series No. 850, Annex 3. Geneva: World Health Organization, 1995. http://www.nus.edu.sg/irb/Articles/WHO%20GCP%201995.pdf.

4. International Conference on Harmonisation of Technical Requirements for Registration of Pharmaceuticals for Human Use. ICH harmonized tripartite guideline: Guideline for good clinical practice E6(R1). International Conference on Harmonisation, 1996. http://www.ich.org/fileadmin/Public_Web_Site/ICH_Products/Guidelines/Efficacy/E6_R1/Step4/E6_R1__Guideline.pdf.

5. United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization (UNESCO). Universal declaration on bioethics and human rights. Paris: 33rd Session of the General Conference of UNESCO, 2005. http://unesdoc.unesco.org/images/0014/001461/146180e.pdf

6. Nuffield Council on Bioethics. The ethics of research related to healthcare in developing countries: A follow-up discussion paper. London: Nuffield Council on Bioethics, 2005. http://www.nuffieldbioethics.org/sites/default/files/HRRDC_Follow-up_Discussion_Paper.pdf.

7. Office of Inspector General of the Department of Health and Human Services. The globalization of clinical trials: A growing challenge in protecting human subjects. Washington, DC: United States Department of Health and Human Services, 2001. http://oig.hhs.gov/oei/reports/oei-01-00-00190.pdf.

8. Parliamentary Office of Science and Technology. “Research ethics in developing countries.” Postnote April 2008, 304. http://www.parliament.uk/documents/post/postpn304.pdf.

9. Ethical issues in international research—setting the stage. Georgetown University Medical Center. http://bioethics. georgetown.edu/nbac/clinical/Chap1.html.

10. Ditton M, Lehane L. “Research ethics: Cross cultural perspective of research ethics in Southeast Asia.” In: Proceedings of the Transmission of Academic Values in Asian Studies Workshop. Edited by Robert Cribb. Canberra: The Australian National University, 2009. http://www.aust-neth.net/transmission_proceedings/papers/Ditton_Lehane.pdf.

11. Teck-Chuan V, Chin J, Campbell AV. “Multinational Research.” In: From Birth to Death and Bench to Clinic: The Hastings Center Bioethics Briefing Book for Journalists, Policymakers, and Campaigns. Edited by Mary Crowley. New York: The Hastings Center, 2008, 107-10. http://www.thehastingscenter.org/uploadedFiles/Publications/Briefing_Book/multinational%20research%20chapter.pdf.

12. Rashid HA. Regional perspectives in research ethics: A report from Bangladesh. Eastern Mediterranean Health Journal 2006;12(Supplement 1):S66-72.

13. Eckstein S. “Efforts to build capacity in research ethics: An overview.” Science and Development Network; 2004 June. http://www.scidev.net/en/science-and-innovation-policy/research-ethics/policy-briefs/efforts-to-build-capacity-in-research-ethics-an-ov.html.

14. Hamadian L, Johansen AK. “Reviewing ethical reviewers: The SIDCER/FERCAP experience.” In: FERCAP @10: In Commemoration of a Decade of Capacity Building in Ethical Health Research in the Asia-Pacific Region. Edited by Atoy M. Navarro and Cristina E. Torres. Pathumthani, Thailand: Forum for Ethical Review Committees in the Asian and Western Pacific Region, 2011.

15. Long A, Kontic AS, Barroso EC, et al. “The regulation and organization of research ethics review.” In: Report of a Comparative International Workshop held at the Faculty of Law, University of Toronto, June 16-18, 2005. Edited by Trudo Lemmens and Tom Archibald. Toronto: Brown Book Company Ltd., 2006. http://www.law.utoronto.ca/documents/Lemmens/workshop%20booklet%20pub%20Feb%202007.pdf.

16. Philippine Health Research Ethics Board Ad Hoc Committee for the Revision of the Ethical Guidelines. National Ethical Guidelines for Health Research 2011. http://www.google.com.ph/url?sa=t&rct=j&q= national%20ethical%20guidelines%20for%20health%20research%202011%2C%2

17. World Health Organization. Standards and Operational Guidelines for Ethics Review of Health-Realted Research with Human Participants, 2011.

Articles and any other material published in the JAFES represent the work of the author(s) and should not be construed to reflect the opinions of the Editors or the Publisher.

Authors are required to accomplish, sign and submit scanned copies of the JAFES Declaration that the article represents original material that is not being considered for publication or has not been published or accepted for publication elsewhere.

Consent forms, as appropriate, have been secured for the publication of information about patients; otherwise, authors declared that all means have been exhausted for securing such consent.

The authors have signed disclosures that there are no financial or other relationships that might lead to a conflict of interest. All authors are required to submit Authorship Certifications that the manuscript has been read and approved by all authors, and that the requirements for authorship have been met by each author.