Vitamin D deficiency (VDD) affects around one billion people globally.[1] It is reflected by low levels of serum 25-hydroxyvitamin D (25-OHD), leading to calcium and phosphate imbalance, bone mineral loss and significant fracture risk. Efforts to address VDD initially focused on temperate countries where serum 25-OHD levels fluctuate to suboptimal ranges during winter and early spring.[2],[3] However, there is a growing focus of concern in tropical countries, which were believed to receive adequate year-round sunlight exposure and are thus previously considered unlikely to harbor VDD. In the Philippines, a study on urban postmenopausal women revealed 36% of the subjects as having inadequate 25-OHD levels.[4]

Ultraviolet ray (UVB) exposure is the main source of Vitamin D in humans.[5] It is assessed by different methods such as observation, skin reflectance with colorimeters, skin swabbing with spectrophotometers, dosimetry with polysulfone films, sunlight diaries and mole inspection. However, these procedures are either not readily available or expensive, or prone to inter-observer variability.[6] In population-based studies, questionnaires remain the most cost-effective way of measuring sunlight exposure.[7] Although no universally-validated version is available for routine use to quantify sunlight exposure, several questionnaires have been formulated and validated in different countries. Of these, only 2 were validated in Asian populations (Hong Kong and Pakistan), and only 3 were done in the context of VDD by correlating questionnaire results with serum 25-OHD.[7],[8],[9],[10]

Currently, there is no existing sunlight exposure questionnaire validated for use in tropical countries such as the Philippines. This study used focus group discussions (FGDs) to explore the attitudes, behaviors and beliefs of urban adult Filipinos on sunlight exposure as an initial step towards the development and validation of a culturally-appropriate sunlight exposure questionnaire.

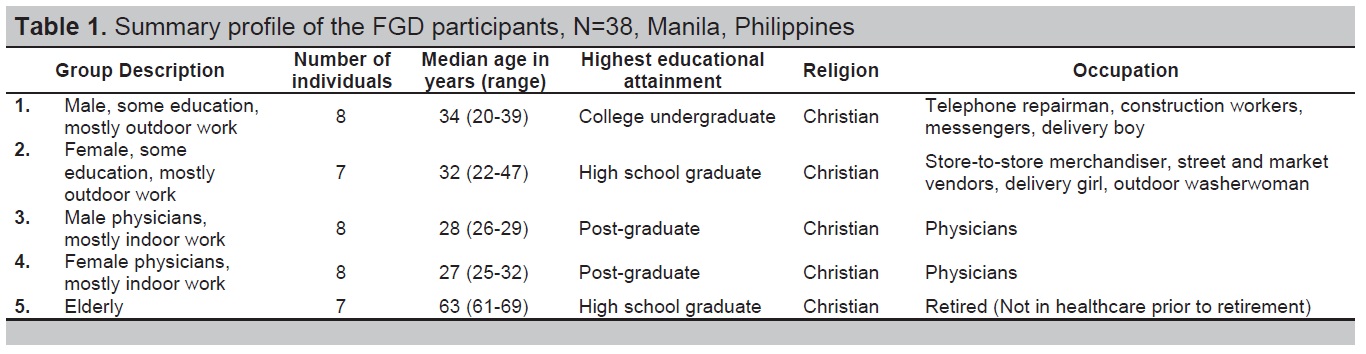

METHODOLOGYThe study included individuals 19 years old or older, who are able to speak and understand the Filipino (Tagalog) language, and who are either living in or working at least 5 days a week in Metro Manila for at least the past 5 years. The FGDs were conducted separately with 5 groups: Group 1, working age (19-60 years old) males with some education and outdoor work; Group 2, working age females with some education and outdoor work; Group 3, working age male physicians with indoor work; Group 4, working age female physicians with indoor work; and Group 5, elderly (60 years and older) individuals. Seven to 8 participants were recruited for each FGD, the recommended number in literature.[11] The participants were recruited from the Philippine General Hospital by two study investigators (MGY and ABU). Table 1 shows the summary profile of the FGD participants.

Table 1. Summary profile of the FGD participants, N=38, Manila, Philippines

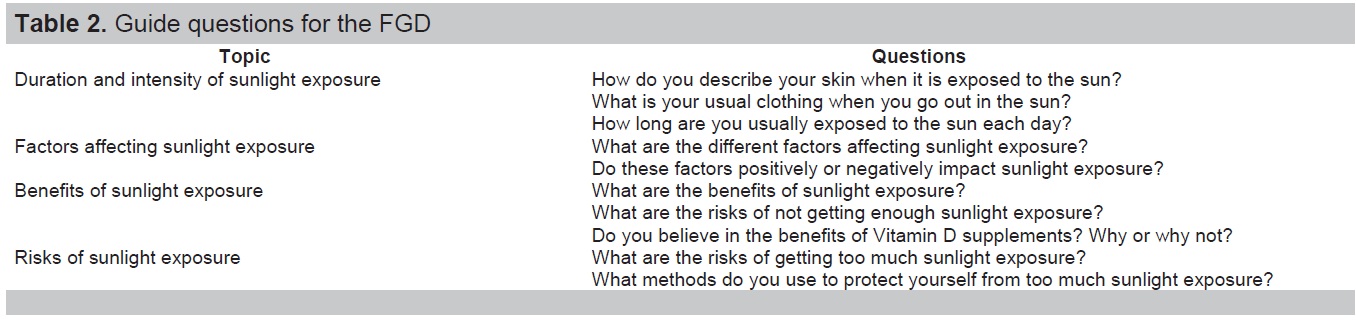

All FGDs were conducted in Filipino (Tagalog) and took place in a quiet room with a facilitator (MGY) and a note-taker (ABU) who did both manual transcription and digital audiotaping of the sessions. Written informed consent was obtained from all participants. Each session commenced with the facilitator first explaining the purpose and outline of the FGD, after which the participants were asked to introduce themselves. The guide questions were formulated by a panel of three endocrinologists, two dermatologists, a health social scientist, an internist and a community medicine physician. These were constructed in a semi-structured, open-ended format (Table 2). Each participant was given a chance to speak, and both verbal and non-verbal responses were noted. The FGDs concluded with the facilitator summarizing the discussion.

Table 2. Guide questions for the FGD

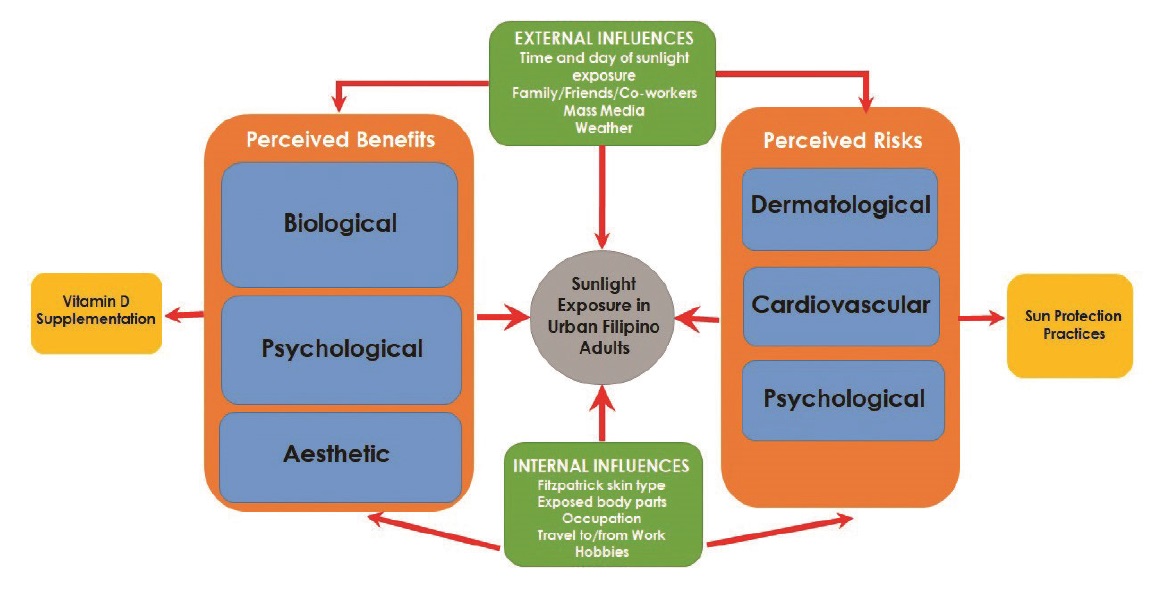

The accuracy of the manual transcripts was verified and cross-checked with the digital audio recordings. The transcribed responses of the participants then underwent qualitative content analysis with quotations being listed anonymously. Both manifest and latent analysis of content data were done. Manifest analysis was first performed by identifying key themes and concepts in the transcripts, after which latent analysis was performed by putting data into categories, with relationships being generated and modified. Emerging themes and sub-themes were further identified by clustering the different categories.[12] The integration of data was based on words, context, frequency, intensity and extensiveness of comments, and specificity of responses. The analyzed FGD results were reviewed by the panel and were used to develop a conceptual framework. The version approved by the majority of the panel (50% + 1, or at least 5 members) was accepted as the final conceptual framework (Figure 1). All qualitative analyses were performed manually.

Figure 1. Conceptual framework on sunlight exposure in urban adult Filipinos

Ethical Consideration

The protocol was approved by the University of the Philippines Manila Research Ethics Board (UPMREB) prior to study commencement. A monetary incentive was provided to all participants as token honorarium.

The 5 FGDs included 38 participants. Each session lasted from 60 to 80 minutes, with the participants being generally cooperative. Females were observed to be more responsive than males; Group 5 participants (elderly) were noted to be the most responsive among all groups while Group 1 participants (outdoor males) were relatively more reserved. Those who attained higher levels of education (Groups 3 and 4) were more open in discussing their opinions. In terms of nonverbal responses, the female and elderly participants used more hand and arm gestures and eye contact while speaking compared to the male participants who were more soft-spoken.

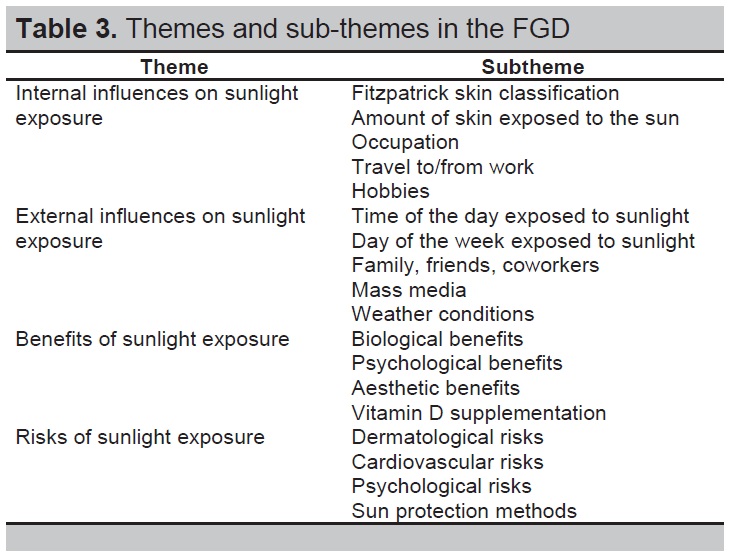

The results of the FGDs are listed below using representative quotes to illustrate the way in which individuals participated in the discussions. Qualitative analysis revealed 4 key themes, each with 4 to 5 sub-themes (Table 3).

Table 3. Themes and sub-themes in the FGD

Internal influences on sunlight exposure

Fitzpatrick skin type. Answers regarding skin type were elicited using the phrase "kapag ang balat ay naaarawan"”(“when the skin is exposed to the sun”). These roughly corresponded to the Fitzpatrick skin phototype classification, which categorizes the response of different skin types to UV light.[13] The participants appeared to possess four Fitzpatrick skin types: Majority had Type IV (“sometimes burn, always tan”) and Type VI (“never burn, always tan”) skin types, while a few had Type I (“always burn, never tan”) and Type III (“sometimes burn, sometimes tan”) skin types.

Amount of skin exposed to the sun. When going out in the sun, males preferred short-sleeved shirts and either shorts or long pants while females preferred either sleeveless tops or short-sleeved shirts and either skirts or long pants. Thus, the face, neck, arms, and sometimes the legs were usually exposed. Some participants believed that this depended on the prescribed work attire.

“Sa kumpanya namin, bawal magtrabaho sa konstruksyon kapag hindi nakasuot ang long sleeves, bota, at helmet.” (“In our company, it is forbidden to work at the construction site when not wearing long sleeves, boots, and a helmet.”) (Male, Outdoor No. 3)

Occupation. A significant difference was seen in the duration of sunlight exposure between the outdoor (Groups 1 and 2) and the indoor and elderly (Groups 3, 4 and 5) participants. The former spent 30 minutes or more to five hours each day exposed to the sun due to the nature of their work. The latter spent as little as 5 minutes each day exposed to the sun and attributed their limited sunlight exposure merely to travel to/from work and errands, respectively.

“Dahil sa trabaho ko bilang repairman sa kumpanya ng telepono, nakabilad ako sa ilalim ng init nang halos buong araw.” (“Because of my work as a telephone company repairman, I am exposed under the heat for almost the entire day.”) (Male, Outdoor No. 1)

Travel to/from work. Travel to work was considered a positive influence on sunlight exposure as most participants walked to work early in the morning and walked back home during late afternoon. Public transport was also perceived to allow more sunlight exposure than private transport.

“Pag nag-aantay ka ng jeep, nakabilad ka sa araw. Ganun din kapag sasakay ka ng LRT. Ang haba kasi ng pila.” (When you are waiting for a jeepney, you are exposed to the sun. The same is true when you are taking the LRT [light rail transit]. The line is so long.”) (Male, Indoor No. 4)

Hobbies. Most participants preferred indoor activities such as shopping, watching television, and surfing the internet, making these a negative influence on sunlight exposure. Only a few engaged in outdoor hobbies such as jogging and outdoor sports.

External influences on sunlight exposure

Time and day of sunlight exposure. For all groups, sunlight exposure took place predominantly during early morning. For the working groups (Groups 1, 2, 3 and 4), this was due to travel from home to work. For the elderly group, this was due to daily activities such as going to the market and bringing grandchildren to school. Most participants reported no significant difference in sunlight exposure between weekdays and weekends.

“Mga 7:00 ng umaga, lumalabas ako para ihatid ang mga apo ko sa paaralan at mamamalengke pagkatapos noon.” (“Around 7:00 in the morning, I go out to bring my grandchildren to school and then proceed to the market after.”) (Elderly No. 1)

Family, friends, and coworkers. The influence of family, friends, and coworkers on sunlight exposure was overwhelmingly negative, with most participants being advised to avoid the sun due to its harmful effects. A recurring theme was the risk of getting darker complexion in the female groups (Groups 2 and 4).

“Sabi ng nanay ko, huwag daw magpaaraw dahil nakakaitim. Dapat panatilihing maputi ang kutis kapag babae.” (“My mother said, don’t get exposed to the sun because it causes darker skin. You need to maintain a fair complexion if you are female.”) (Female, Indoor No. 2)

The elderly participants stated that sunlight exposure was heavily dependent on the type of activities they accompanied their younger family members to.

“Depende sa gustong gawin ng mga anak at apo ko. Kung gusto nila magpaaraw, sasama ako. Kung gusto nila pumunta sa mall, sasama din ako.” (“It depends on what my children and grandchildren want to do. If they want to go out in the sun, I would go with them. If they want to go to the mall, I would also go with them.”) (Elderly No. 3)

Mass media. The influence of mass media on sunlight exposure was similarly negative. The participants believed that this is significant in Philippine society where fair skin is valued.

(Verbatim in English): “They always advertise whitening products on TV. That’s why no one goes out in the sun anymore.” (Male, Indoor No. 1)

Weather. Most participants were willing to be out in the sun more during cloudy weather as opposed to extremely sunny weather, as they tried to avoid the heat.

“Mas maaliwalas kapag maulap. Ayokong lumabas kapag masyadong maaraw.” (“It’s more comfortable when it’s cloudy. I don’t want to go out when it’s too sunny.”) (Female, Outdoor No. 5)

Perceived benefits of sunlight exposure

The perceived benefits of sunlight exposure fell under three categories: biological, psychological and aesthetic.

Biological benefits. For the participants, the purported biological benefits of sunlight exposure included favorable effects on bone health and faster recovery from illness. Conversely, many of them believed that lack of sunlight exposure is a detriment to the immune system and makes one sicklier.

“Kapag hindi ka nagpapaaraw, lalo kang madaling kapitan ng ubo’t sipon.” (“When you don’t get exposed to the sun, you’ll be more prone to cough and colds.”) (Elderly No. 6)

Psychological benefits. The psychological benefits of sunlight exposure included feeling happier and livelier. Some participants believed that this is due to increased physical activity when one is outdoors.

Aesthetic benefits. The aesthetic benefits of sunlight exposure included getting a rosier complexion, which the participants attributed to improved circulation. Some participants with skin types that tan also believed tanning gave them a better and more “exotic” appearance.

(Verbatim in English): “I look thinner and sexier. I also like the beauty of a tan.” (Female, Indoor No. 3)

Vitamin D supplementation. Almost all participants did not take Vitamin D supplements, which they attributed to the abundance of sunlight in the Philippines. Some believed that supplements are effective only if partnered with sunlight exposure.

“Hindi ako umiinom ng supplement kung hindi naman kailangan. Maaari pa itong magdulot ng ‘di magandang epekto sa katawan.” (“I don’t take supplements if these are not necessary. They can even cause harmful side effects to the body.”) (Female, Outdoor No. 1)

“Kailangan ng balanse. Magpapaaraw ka sa umaga at iinom ka ng supplement sa gabi.” (“There should be balance. You get exposed to the sun during the day and take supplements at night.”) (Elderly No. 5)

Perceived risks of sunlight exposure

Similar to the perceived benefits, the perceived risks of too much sunlight exposure can also be classified under biological and psychological categories. However, the biological risks clearly fell under two sub-categories: dermatological and cardiovascular.

Dermatological risks. Most of the participants were familiar with and used English terms for the different dermatological conditions caused by too much sunlight exposure, such as “sunburn,” “skin cancer,” and “skin allergy.” The exceptions were prickly heat rash (termed “bungang-araw”) and photoaging (termed “pangungulubot ng mukha” or “wrinkling of the face” by the participants.)

Cardiovascular risks. The cardiovascular risks of too much sunlight exposure included hypertension, dizziness and heat stroke. Some participants believed that this is caused by unfavorable changes in the body’s circulatory system.

“Kapag masyadong matagal sa ilalim ng araw, lalapot ang dugo mo at magiging high blood.“ (“When you are under the sun for too long, your blood will become more viscous, leading to hypertension.”) (Female, Outdoor No. 1)

Psychological risks. The psychological risks of too much sunlight exposure included discomfort from sweating and fear of getting darker skin. These were especially emphasized in the indoor female group (Group 4).

(Verbatim in English): “I feel uncomfortable when I am sweaty. I also develop low self-esteem when I get darker skin because in the Philippines, you can get bullied for that.” (Female, Indoor No. 7)

Sun protection methods. The participants utilized different methods of sun protection. The use of caps and hats was a common feature of outdoor males. This group was also the only one not using sunscreen, as many thought these were only for women. Umbrella use, meanwhile, was found in most females. Active shade-seeking was a common feature of the outdoor groups due to the nature of their work. Shades or sunglasses were the least commonly-employed form of sun protection and were mostly worn for fashion purposes instead.

“Hindi ako gumagamit ng sunblock. Di ba pangbabae lang ‘yun?” (“I don’t use sunblock. Isn’t it only for girls?”) (Male, Outdoor No. 4)

(Verbatim in English): “It’s a cultural thing to not actively seek shade because we are in a tropical country.” (Female, Indoor No. 5)

Conceptual framework

The end result of the FGDs was a conceptual framework explaining the attitudes, behaviors, and beliefs of urban adult Filipinos on sunlight exposure (Figure 1). In general, sunlight exposure in urban adult Filipinos was influenced primarily by two main factors: internal and external. Internal factors included the Fitzpatrick skin type, amount of body parts exposed to sunlight, type of occupation, travel to/from work and hobbies. External factors included the time of the day and day of the week exposed to sunlight, weather conditions, mass media, and the influence of other people such as family, friends and colleagues. Both internal and external factors, in turn, led to perceived risks and benefits. Perceived benefits were biological, psychological or aesthetic; whereas perceived risks were dermatological, cardiovascular or psychological. The perceived benefits (or lack of) of sunlight exposure influenced an individual’s attitudes towards Vitamin D supplementation, whereas the perceived risks of sunlight exposure influenced an individual’s attitudes towards the need for sun protection.

In this study, we explored the attitudes, behaviors, and beliefs of urban adult Filipinos on sunlight exposure. Our study is unique in so far as no other qualitative research has been conducted in a similar setting and population to investigate concepts and notions about sunlight exposure. Urban residents were prioritized as air pollutants in cities absorb UVB, thus reducing the amount that reaches the earth’s surface.[14] This may partly explain the lower serum 25-OHD levels consistently found in urban populations across Asia.[15],[16]

The first theme involved internal influences on sunlight exposure in the participants, which are factors usually inherent to the individual. In terms of Fitzpatrick skin type, the participants’ responses conformed to the general perception of Southeast Asian people being darker-skinned compared to Caucasians. Since melanin is known to absorb UVB, the former may require a greater degree of sunlight exposure to synthesize a comparable amount of Vitamin D.[17] Indoor occupations and hobbies negatively impacted sunlight exposure, while public transport positively impacted sunlight exposure. The influence of public transport was striking given the generally perceived lack of transport infrastructure in the Philippines.[18]

The second theme involved external influences on sunlight exposure, which are extrinsic to or non-modifiable by the individual. The relative constancy of the participants’ sunlight exposure duration, regardless of day of the week or month of the year, conformed to the flat seasonal profile of tropical countries, in contrast to temperate countries with distinct seasons and climates. Family and friends, mass media and sunny weather negatively impacted sunlight exposure, while cloudy weather positively affected sunlight exposure. The significant influence of family attested to the strong kinship and social ties of Filipinos.[19] The considerable influence of mass media, on the other hand, can be explained by urban residents having better access to technology compared to their rural counterparts.

The third theme involved the perceived benefits of sunlight exposure. These were grouped into three main categories: biological, psychological and aesthetic. One observation was the lack of a local term equivalent for VDD, as many participants attempted to come up with concepts such as “kakulangan ng bitamina” (“lack of vitamins”) and “panghihina ng buto” (“weakening of the bones”). The fact that most participants did not take Vitamin D supplements was also another interesting observation given the widespread advertising of supplements in the Philippines.

The last theme involved the perceived risks of sunlight exposure, also grouped into three categories: dermatological, cardiovascular and psychological. While the dermatological and cardiovascular risks were consistent with scientific literature, the psychological fears of getting darker skin highlighted the common Filipino psyche of wanting to attain fairer skin, which is perceived as superior.[20] Sun protection practices, as a whole, were also more common in hotter climates. We found noticeable sex differences, with men preferring to use caps and women preferring umbrellas. Many participants, however, were not aware of the concept of sunlight protection factors (SPF) for sunscreens, given that a mere potency of SPF 8 has been shown to reduce Vitamin D production by as much as 90%.[21]

Member homogeneity is important to focus groups as it allows the individual participants to be more comfortable with each other, and in turn, achieve a high degree of group interaction.[22] However, the pressure to conform to the ideas of others may have also induced socially desirable behavior, which has been termed the “acquiescence effect” in literature.[23] In Filipinos, this is called “pakikisama” (“to go along”), and is evident in the fact that few dissenting opinions were noted in the FGDs.[24] Furthermore, the responses may have also been influenced by the fact that the sessions were conducted in the proximity of a health center, and as such, the participants possessed a relatively strong health-seeking behavior (although we did not have any data regarding health resource use). Strong health-seeking behavior is usually associated with higher levels of self-management.[25]

Aside from the physicians, the rest of the participants were also relatively well-educated (being at least high school graduates) and hence were relatively familiar with the concepts discussed. Many terms were expressed verbatim in English regardless of FGD group.

The study utilized both manifest and latent analyses of content data. Manifest data refers to the tangible or concrete surface content, while latent data involves the underlying meaning behind the actual information. The advantages of manifest analysis are its ease of use and reliability (as it is evaluated at face value), but at the expense of lower validity. Latent analysis, on the other hand, possesses stronger validity but requires greater comprehension skill. It also has lower reliability due to the possibility of multiple interpretations. Hence, combining the two analysis types enables qualitative researchers to draw from the strengths of both techniques.[26]

One limitation of the study was the lack of a pretest of the focus group instrument prior to the actual FGDs. Another was the performance of manifest and latent analyses by only one investigator, although the final analyzed results were reviewed, revised and eventually approved by the entire panel. Due to health reasons and logistic difficulties, we were also unable to recruit very elderly (above 70 years old) participants, one of the groups most at risk for VDD. Since serum 25-OHD levels were not tested prior to the FGDs, we were likewise unable to determine whether any of the participants have known VDD. Moreover, none of the FGD participants were night shift workers, and we were unable to recruit participants of other religions, such as hijab-wearing female Muslims.[27] According to the National Commission on Muslim Filipinos in 2012, Muslims are estimated to comprise 10.7% of the country’s population.[28]

The attitudes, behaviors and beliefs of urban adult Filipinos on sunlight exposure are influenced by both internal and external factors that in turn lead to perceived risks and benefits. An increased awareness of these factors is necessary to establish future recommendations on proper sunlight exposure in this population. The study results will be used to develop and validate a culturally-appropriate sunlight exposure questionnaire.

Statement of AuthorshipAll authors certified fulfillment of ICMJE authorship criteria.

Author DisclosureThe authors declared no conflict of interest.

Funding SourceThe study was made possible through a grant from the Philippine Society of Endocrinology, Diabetes and Metabolism.

[1] Holick MF, Chen TC. Vitamin D deficiency: A worldwide problem with health consequences. Am J Clin Nutr. 2008;87(4):1080S-6S. PubMed CrossRef